Text by Sarah Burchard

Images by Camille Huguenot and Chris Rohrer

Take a look at the bottles lining the shelves of your local wine shop. Because the U.S. government allows winemakers to add more than 72 chemicals to their products, practically all of the wine on the market contains additives, coloring agents, and synthetic yeasts used by high-tech winemakers to manipulate its color, fragrance, and flavor. Luckily, delicious wines without chemicals do exist. The difficult part is finding them.

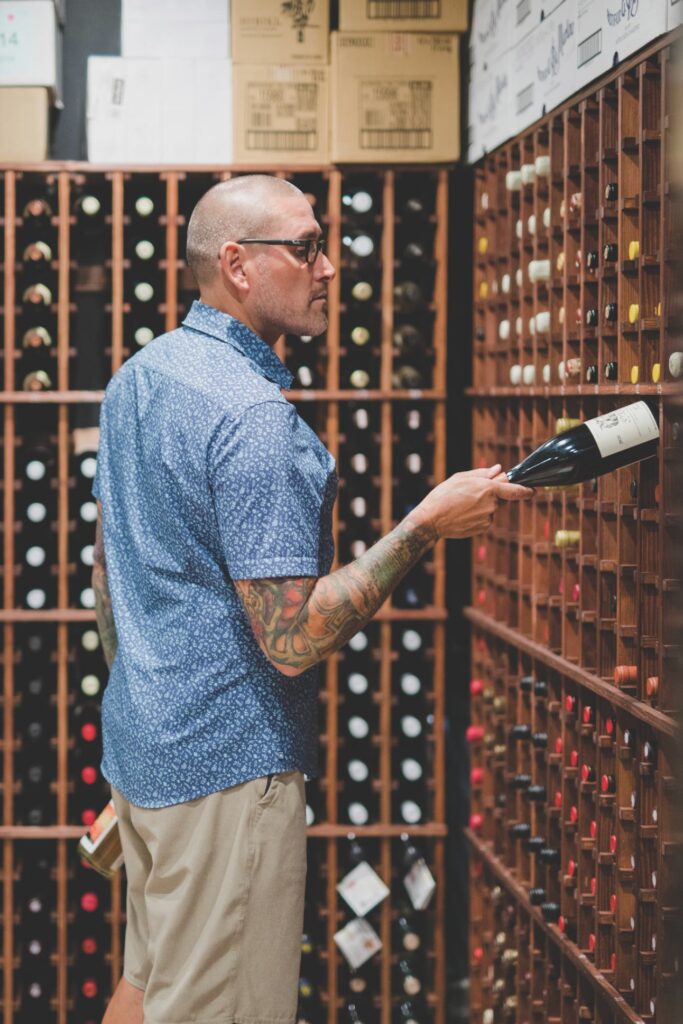

Rick Lilley became a natural wine advocate after traveling to France in 2016 and 2017 with the sales team from wine importer Kermit Lynch, who, in the ’70s, was among the first U.S. wine importers to champion natural wine and has since become one of the most trusted names in the wine business. When Lilley returned from France, he urged distributers to carry Lynch’s wines so that he could offer them at 12th Ave Grill, where Lilley served as wine director. The more natural wines Lilley tried, the more he lost his taste for conventional, New World winemaking. When guests began asking Lilley where they could purchase the wines he was pouring, he came up with the idea for a natural wine shop.

When he and his wife, Elaine, opened Brix and Stones—a wine shop and cigar lounge tucked inside an auto-collision shop on Waimanu Street—in early 2020, they were committed to transparency. More than a third of the inventory consists of natural and low-intervention wines made with organic grapes and no additives or chemicals. In spring 2023, the Lilleys plan to expand the business by opening a wine and whiskey bar below the shop and offering tastings and education on the wines and spirits it carries. Guests will have the opportunity to learn how the grapes are grown, how the wines are made, and what exactly is in them.

Natural wines begin on biodiverse vineyards, where the grapes are grown without pesticides and cultivated alongside animals, trees, and other crops to maintain the land’s ecological balance, which in turn produces clean wines that are high in antioxidants and other nutrients. Low-intervention wines contain low levels of sulfur dioxide, a stabilizer and preservative; wines that are 100 percent natural omit sulfur dioxide altogether. Both are fermented with wild yeast as opposed to “designer” yeasts created to manipulate the flavor and fragrance of wine. There is no sugar added to increase the alcohol content, nor is there water added to decrease alcohol content. Unlike conventional wines, which are often filtered with egg whites or fish bladders, natural wines are 100 percent vegan.

Natural wine may be seeing a rise in popularity over recent decades, but Georgians have been producing wine using natural methods for the past 8,000 years. The knowledge was almost lost during the Soviet reign, when monocropping was enforced, and most of the world’s vineyards—which also produced wine by traditional means for thousands of years—began introducing synthetic chemicals with the rise of industrial agriculture after World War II.

The natural wine movement began in 1965, when winemakers from the French province of Beaujolais returned to their grandfathers’ methods of farming organically and making wine without manipulation. Once U.S. wine importers discovered wines like these in France, the movement migrated to New York and California.

In 2001, Alice Feiring was the first wine journalist in the U.S. to advocate for natural wine. She called out wine critic Robert Parker and his 100-point wine-scoring system, arguing that it encourages a formulaic approach to winemaking, and also chided large wine corporations for influencing sommeliers to train themselves and their guests to view conventional wines as “correct” and natural wines as flawed. By 2010 natural wine was trending in the U.S., although natural wine producers still represent only a tiny fraction of the industry.

Early adopters fear that too much emphasis on the word “natural” will encourage winemakers to capitalize on a trendy new buzzword. Prices are beginning to creep up due to demand, and wine buyers are finding it increasingly difficult to source these wines due to their already limited availability. And with the exception of anomalies such as Santa Cruz’s Bonny Doon Vineyard, which began including ingredient lists on its bottles in 2007, it is difficult for consumers to know whether a wine is natural or not by its label—the industry doesn’t require winemakers to disclose their ingredients.

Luckily, in Kakaʻako, Brix and Stones is there to help. “There are a handful of importers dedicated to natty wines,” Lilley says. “Once I get familiar with them, I’m able to learn more about the producers they carry and their philosophies. Since the term ‘natural’ is unregulated, you really have to decide on your own what your beliefs are.”