Text by Mitchell Kuga

Images by Mark Kushimi and courtesy of the Honolulu Museum of Art

The abundance of artwork hanging in Jean and Robert Steele’s Hawaii Kai condo traces a genealogy of African American printmaking. There are pieces by pioneering artists like James Lesesne Wells, a graphic artist and printmaker influential to the Harlem Renaissance, and Romare Bearden, whose vibrant collages depict the Black lived experience. Yet there’s one small piece in the couple’s bedroom that stands apart from the rest: Tony Northern’s Three African Women in Profile, which the artist painted on the side of a cardboard box. Robert purchased the painting in 1968 for $10 from an art gallery in Harlem, but not before asking his wife for permission first. Jean winced at the price. They were both graduate students at the time, with Robert interning at the Harlem Hospital, and the purchase would significantly cut into their weekly grocery budget. After further discussion, she acquiesced, launching—to both of their surprise—an over five-decade journey of collecting works on paper by African American artists.

“Forward Together: African American Prints from the Jean and Robert Steele Collection,” shown in two rotations at the Honolulu Museum of Art through September 2024, comprises a significant segment of that collection. Acquired by the museum as a partial gift from the Steeles, the exhibition’s 55 prints by 25 artists spans four decades and more than doubles the African American artists represented in HoMA’s permanent collection. “I don’t think one can appreciate or understand the breadth of American art unless it includes the contributions of Native Americans, Asian Americans, [and] African Americans,” says Robert, who in 2020 donated 100 pieces from their collection to Yale University, where he earned his Ph.D. in clinical community psychology. “I see part of our mission as completing or rounding out that story.”

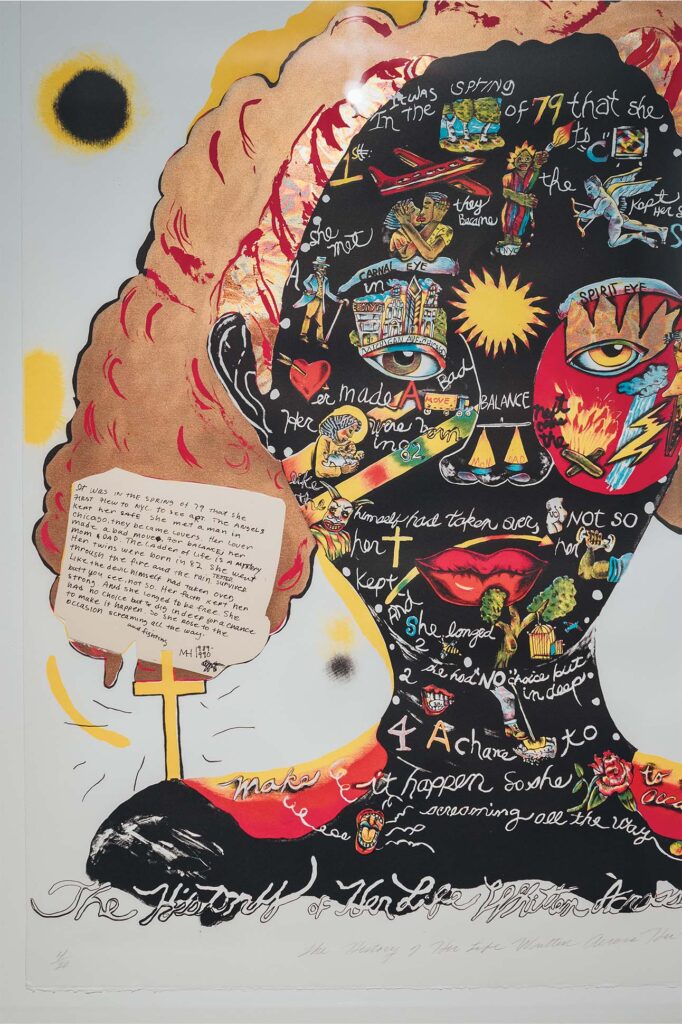

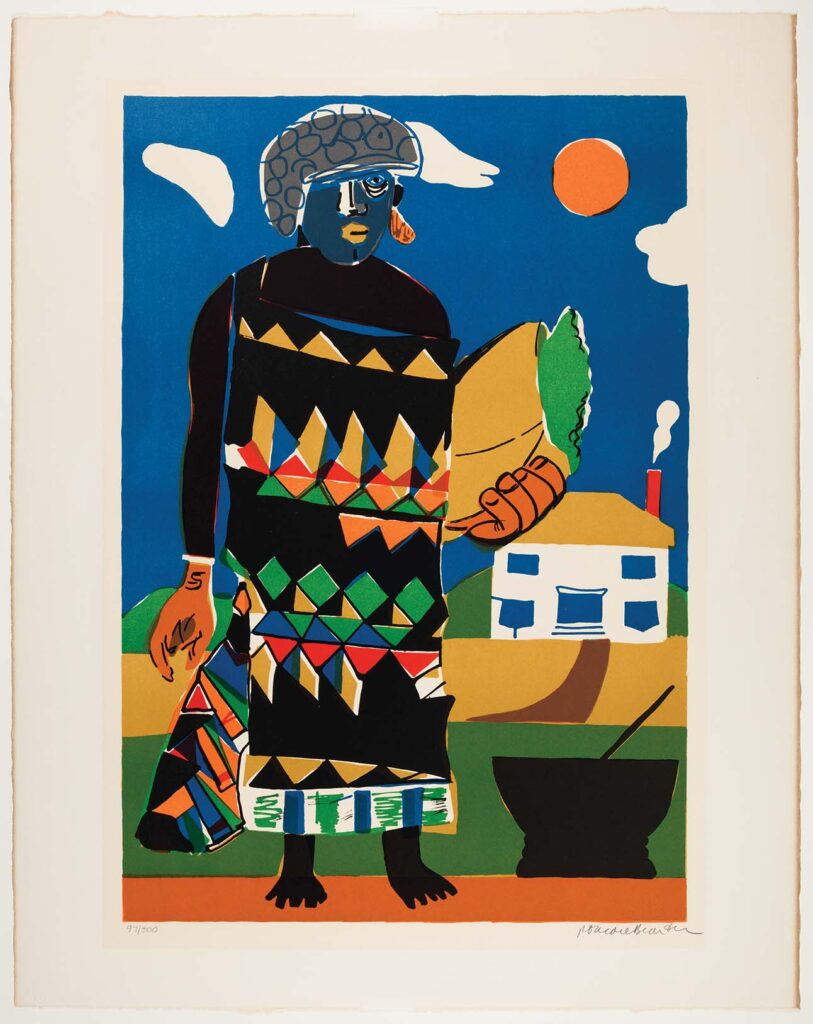

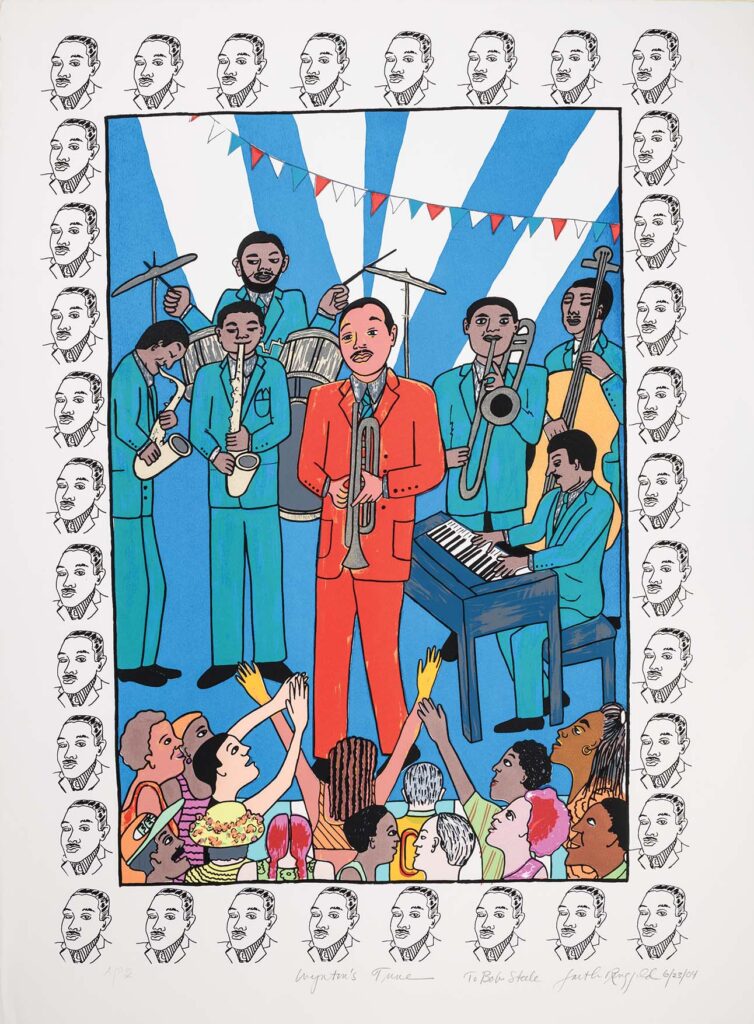

The acquisition reflects the Steeles’ taste as collectors, favoring figurative works in striking colors and various mediums by artists like Faith Ringgold, David Driskell, Sam Gillian, and Joyce Scott. The couple met in 1967 while attending Episcopal theological school, and themes related to spirituality, social justice, and Black history run throughout the collection. Jacob Lawrence’s Forward Together, an expressive silkscreen that inspired the exhibition’s title, pays homage to Harriet Tubman. Ringgold’s Somebody Stole My Broken Heart depicts the psychedelic exuberance of a jazz club.

HoMA’s director and CEO, Halona Norton-Westbrook, calls the Steeles’ gift “transformational,” stressing not only the diversity of the collection but the intimate nature of how it came together. “That component of how they collect through building friendships and relationships with artists—it lends this depth to it,” Norton-Westbrook says. “There’s something extremely special about a collection that grows out of personal relationships with artists that have been built over time.”

The Steeles cultivated many of those relationships while Robert served as the executive director of the University of Maryland’s David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora, from 2002 to 2012. (Prior, he was a professor and dean at the university’s College of Behavior and Social Sciences.) It was a unique position for someone who had never taken an art history class, yet Robert’s personal history of art collecting proved he was up to the task. Over the decades, the Steeles embarked on a self-directed education in the arts, joining collectors’ clubs, attending lectures, scouring catalogs and art books, and visiting artists’ studios. In 2012, the Driskell Center launched “Successions,” a traveling show that featured 62 prints from the Steeles’ collection. The show garnered Robert, who deemed Driskell “the father of African American art history,” national attention.

The Steeles moved to O‘ahu in 2016, where their daughter lived and where Jean’s mother was born and raised. It’s a connection dating back to 1852, when Jean’s great-great-grandfather emigrated there from Portugal. While growing up in California, Hawai‘i references peppered Jean’s household. “If a picture on the wall wasn’t straight, it was kapakahi (crooked),” she says. “We had all these words and place names.” In 2020, Jean and Robert visited HoMA’s “30 Americans.” It featured works by 30 contemporary artists, which included Mickalene Thomas, Kara Walker, and Carrie Mae Weems, connected through their African American cultural history. The show impressed the couple, and they began speaking with the museum about expanding the African American artists represented in its permanent collection. The conversations eventually prompted HoMA’s director of curatorial affairs, Catherine Whitney, to make the trip to survey the bulk of the Steeles’ collection, which numbered in the hundreds and sat in a temperature-controlled storage facility in Maryland.

The Steeles admit that it’s hard to part with certain pieces from their collection—nearly each one triggers an anecdote or distinct memory—but after 55 years of collecting, they were already in the process of deaccessioning. It’s also not lost on them that HoMA’s acquisition brings them physically closer to their collection. “There’s an appeal of having some of these pieces close by,” Jean says, chuckling. “Now we can actually go see them.”

The real collection, anyway, is hanging in the couple’s condo, including an original artwork by Ringgold that Robert was gifted after retiring from the Driskell Center. It features an illustration of Robert’s face looking skyward, backgrounded by a watermelon motif. (In addition to art, stamps, and coins, Robert also has an affinity for watermelon-themed objects.) Framing the piece is a message from the artist in the style of her signature story quilts: “Rainmaker that you are, you’ve made the Driskell Center a star. And your art collection is unique and still growing as we speak.”