Text by Jasmine Reiko

Images by Keatan Kamakaiwi

Artwork courtesy of Nainoaikapoliokaehukai Rosehill

When the Hawai‘i Island painter Nainoaikapoliokaehukai Rosehill returned to his hometown of Puna from art school on the U.S. mainland in 2018, his homecoming was a period of deep change, isolation, and uncertainty. That year, 10-meter-high lava flows ran through Lower Puna, covering 13.7 square miles and creating 875 acres of new land. His community lost homes and everyday gathering places that can now only be remembered in mele (songs), words, and photographs.

“I started thinking about all these places that I grew up in not existing anymore, all of these memories that no longer have physical attachments to them,” Rosehill says. “These are all the beautiful moments in my mind that I can return to.”

Surrounded by a family of musicians and dancers growing up, Rosehill was the first to pursue the graphic arts as more than just a hobby. While at North Park University in Chicago, he found himself drawn to paint. Marveling at a professor’s extensive catalog of pigments, the burgeoning artist considered each hue a lesson in its own right: He started to see color as sculptural and historicized, an understanding of material that would underscore his later works.

Soon after, Rosehill began taking burnt sienna, a color traditionally used as an understudy base layer, and bringing it into the foreground, an ongoing gesture throughout his body of work: drawing forth something meant to be buried underneath. During the pandemic, he collected rocks from a beach that no longer exists and gathered plants, shells, and organic dyes from other sites of personal significance. He did not have an array of pigments as his professor did, but he had a working archive of materials to inspire him. Rosehill takes great care to list these materials, as he does in “Deiwos” (2022): “hili kukui, alaea, hua moa, pau kukui, limu akiaki, wai ulu, pilali, kulukulu‘ā, synthesized yellow iron oxide derived from an early 20th-century shotgun, mineral pigments, and soot.”

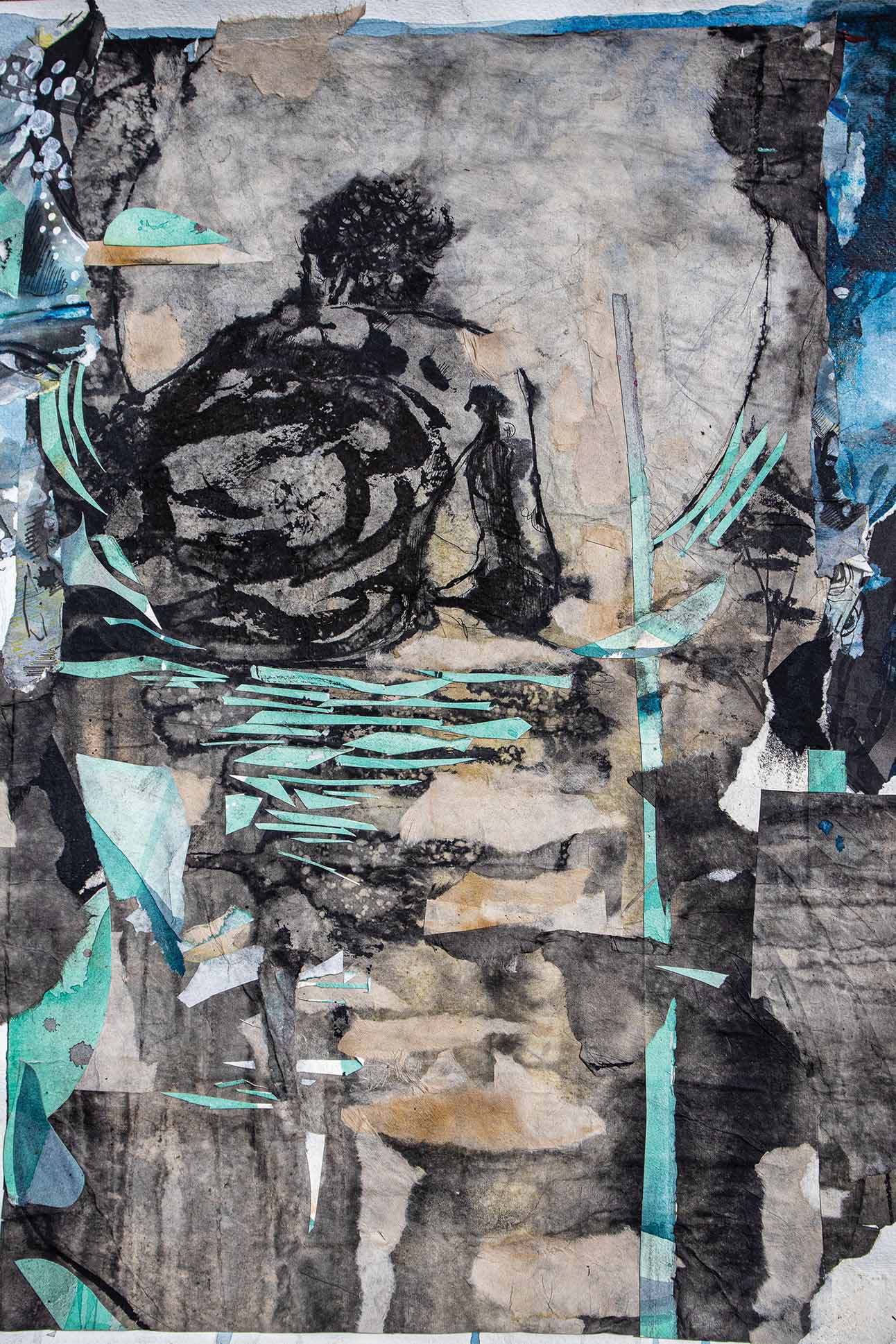

Fusing inspiration from contemporary Chinese painters, such as Xu Longsen, with his studies and research on mo‘okū‘auhau (genealogies) and mo‘olelo (stories), Rosehill draws from many sources at once when assembling his mixed media works, allowing them to emerge like a memory in the finished piece. “Ikua” (2022) stands as an anchoring point for Rosehill, a dialectic of form and Native symbolism that deconstructs two paintings from 2019 and meshes them together to become one. An inventory of its media alone suggests a slew of disparate stories: “painted with the burnt bones of owls and elk killed by last year’s winter, fermented mango, turmeric, expired tattoo ink, taro (‘ula‘ula poni and mana ‘ōpelu) dye, and acrylic paint on handmade mulberry paper.”

The places significant to Rosehill’s identity as Kanaka ‘Ōiwi (Native Hawaiian) have radically changed in the past century. Keeping personal and subjective records of joyful moments and the community lifestyle of Puna remains incredibly valuable to him. “It’s about connecting the family album into the role of the mele and the oli (chant) as pre-photography methods of things through memory that we love persisting,” he says. “Songs are mechanisms for us to tap back into those memories, and art is a way for us to express those not-so-physical feelings of those places, and having those places become immortalized.”

One of the only vestiges of the Kalapana community that survived the 1990 Kīlauea lava flow of his parents’ time is the Star of the Sea Painted Church founded by Belgian Catholic missionary Father Evarist Gielen, built between 1927 and 1928 on the shoreline of Kaimū Beach. (It was lifted and relocated from Kalapana by a trailer truck to the end of Highway 130 ahead of the advancing lava flow.) Elaborate, life-sized paintings adorn the church’s Colonial Revival-style interior. They include Gielen’s depictions of scenes and religious characters from the Catechism of the Catholic Church, all painted at night by the light of an oil lamp. In 1978, Hilo artist George Lorch was commissioned by Father Joseph Edward Avery to paint a series of frescoes depicting traditional teachings of Catholicism on the existing panels. Lorch created scenes inspired by the seven sacraments, the Virgin Mary, saints, and angels. Father Avery, a priest from Massachusetts, spoke ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i fluently, and some of the featured scripture painted by George Lorch is written in Hawaiian.

Each pew has a plaque with the names of the people who used to sit there, including Rosehill’s great-great-grandparents, who were among the Painted Church’s original parishioners. “It is the only physical thing that exists in that area that speaks to the village being there before,” he says. “It being a church and being filled with paintings and being connected to me through my family—it feels significant.”

Rosehill considers it “an architectural equivalent to a photo in a family album.” “I can enter and go inside,” he says. “We are intimately tied to that place to try and figure out what that means, how to keep that relationship alive today.” Like the landscape itself—more often in flux than dormant over the past century—the church is “a manifestation of diaspora,” he explains, “where you are there, but you can never really be there. It’s an impenetrable barrier between the ideal and the material world that mimics a lot of what religious art speaks to. The impassable barrier between the divine and the temporal. Eternity and what is mortal.”

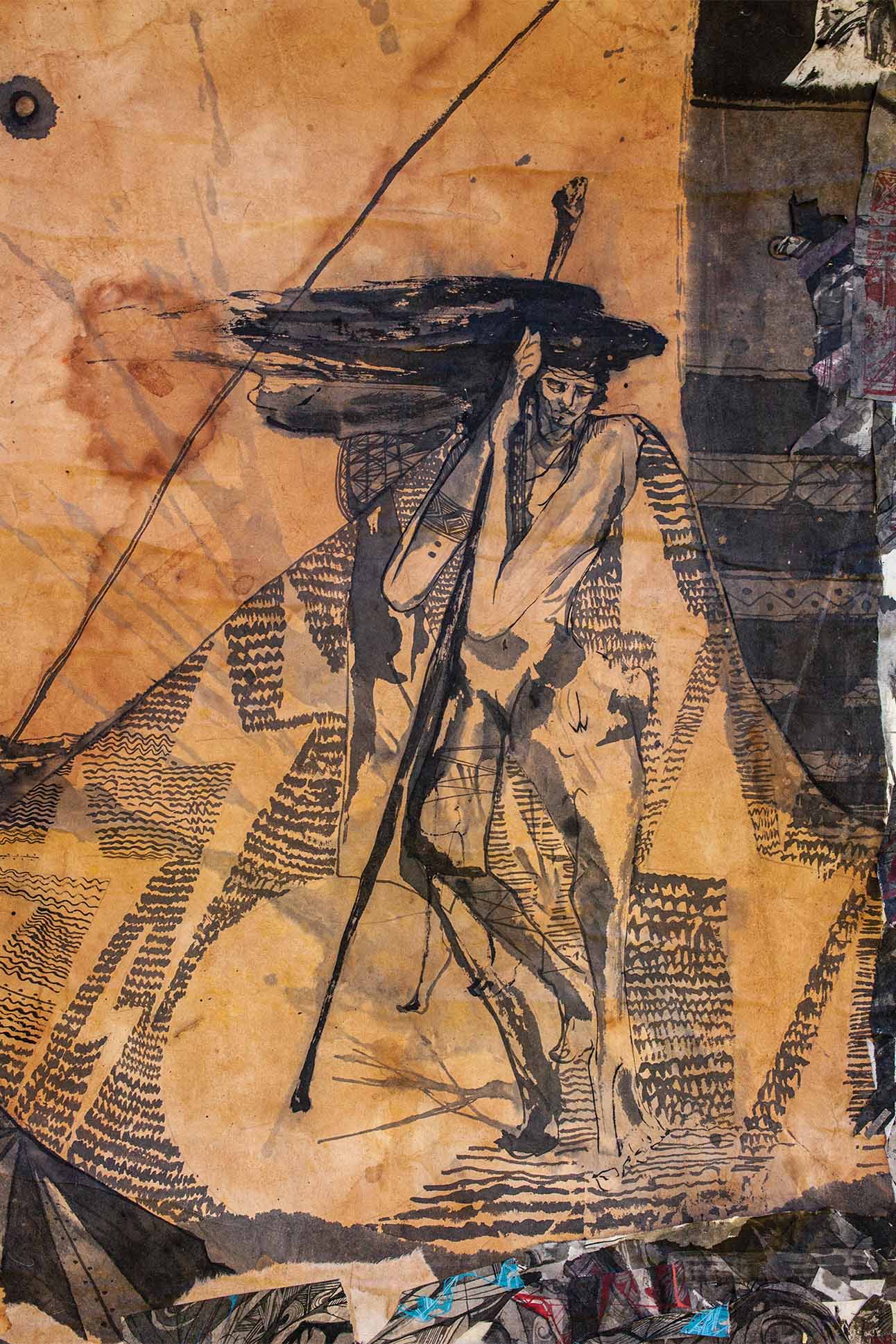

Kihawahine, the high-ranking Maui chiefess who was transformed into a mo‘o (lizard) upon her death, lives again in Rosehill’s painting “The Passion of 40,000 Rivers” (2023), reflecting where he stands now in his artistic practice. Kihawahine approaches the viewer with an authoritative presence, embodying a shifting and expressive power over the land. “The heavens sough and murmur above her,” Rosehill says of its composition. “Out of death, she rises, stronger than ever; she is a testament, a memory, a lesson, a river of change.”

Like photo albums binding together places lost, people passed, and time elapsed, Rosehill seeks to connect everything around him: “I would love to show that through my art—that quality of living. To live in a way that is so moving that people, after you pass, still carry you with them.”