Text by Mitchell Kuga

Images by Jana Dillon, Lee Jaffe, and Christopher Makos

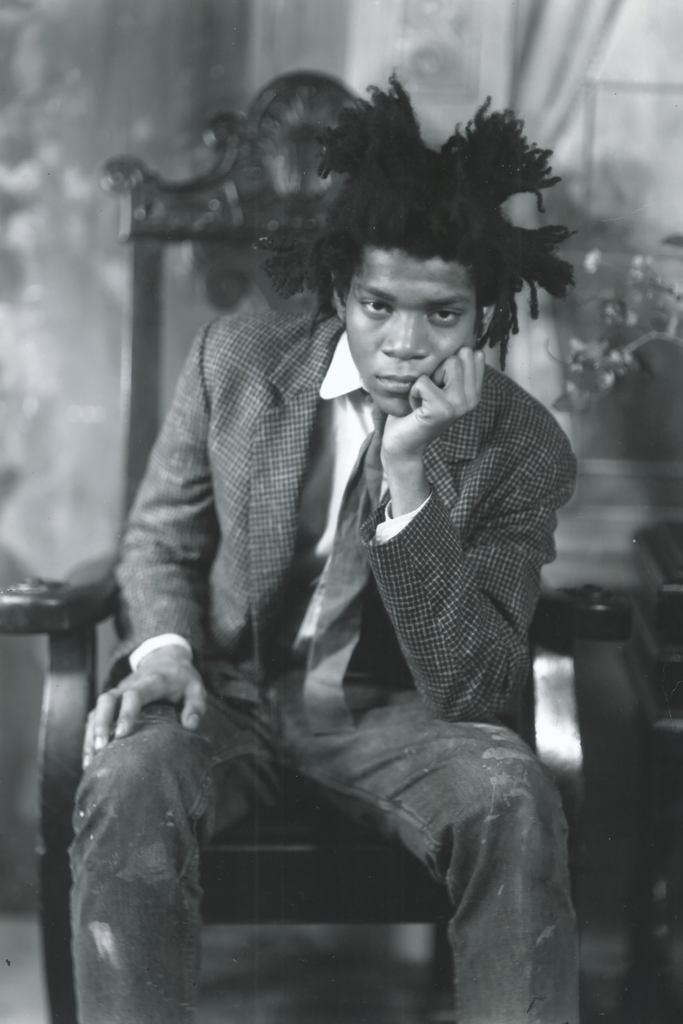

You’d be hard pressed to find an artist more emblematic of New York City’s countercultural spirit in the eighties than Jean-Michel Basquiat. His paintings, which poetically juxtapose elements of street art, Neo Expressionism, and hip-hop, both reflected and fueled the chaos of New York at the time, helping legitimize graffiti as an art form. But the artist, who died of a heroin overdose in 1988, at the age of 27, found a home in a very different place toward the end of his life: Hana, Maui.

Basquiat made visits to the small remote town on the eastern edge of Maui during the summers between 1984 and 1988—a seeming refuge from the pressures of having catapulted to the red-hot center of the New York art world, which coincided with an increasingly dangerous drug habit. Myke-Embe Cappadona didn’t know any of this when he remembers first meeting Basquiat sometime in the early eighties on Hana Highway, the beautifully twisting and often terrifying road that separates Hana from the rest of Maui.

As he recounts in an essay titled “Jean-Michel & Basquiat,” Cappadona was walking along the highway selling pot, flashing baggies at anyone driving by with long hair; Basquiat, who remembered buying pot from Cappadonna on a previous visit, was cruising by with friends. They pulled over, bought some weed, and shared a joint on the side of the road, talking story about New York, where Cappadona lived shortly after serving in the Marine Corps. “I don’t recall much of the details of our conversation,” Cappadona writes, “but I do remember that they were a bunch of happy guys having a goof in a beautiful place, enjoying their life, just like I was.”

Born one month apart on opposite sides of the Hudson River—Cappadona in New Jersey, Basquiat in Brooklyn—the two became fast and easy friends. “Each and every visit we had together would revolve around smoking cannabis,” he writes. “I would take him to some gorgeous place which we referred to as ‘joint points,’ either a place to swim in one of the many streams around Kipahulu, or somewhere with a breathtaking view.”

Throughout their friendship, Cappadona had no idea that Basquiat was an internationally renowned artist; for a while his lodging, a foam pad in a mutual friend’s fruit shack, suggested otherwise. But there were clues. He noticed the “prankster” constantly writing or scribbling on things: scraps of paper lying around Cappadona’s car; Cappadona’s window, in crayon; an antique cabinet that had belonged to Cappadona’s weaving mentor. “Often these writings said some peculiar things,” Cappadona writes, noting that most of his “doodles” ended up in the trash.

Cappadona did eventually ask Basquiat what he did in New York, and he responded without hesitating: “I am a painter.”

“I paint houses too sometimes,” Capadonna replied. “But I don’t like it. It’s a shitty job.”

Basquiat smiled, happy to be just another guy in Hana.

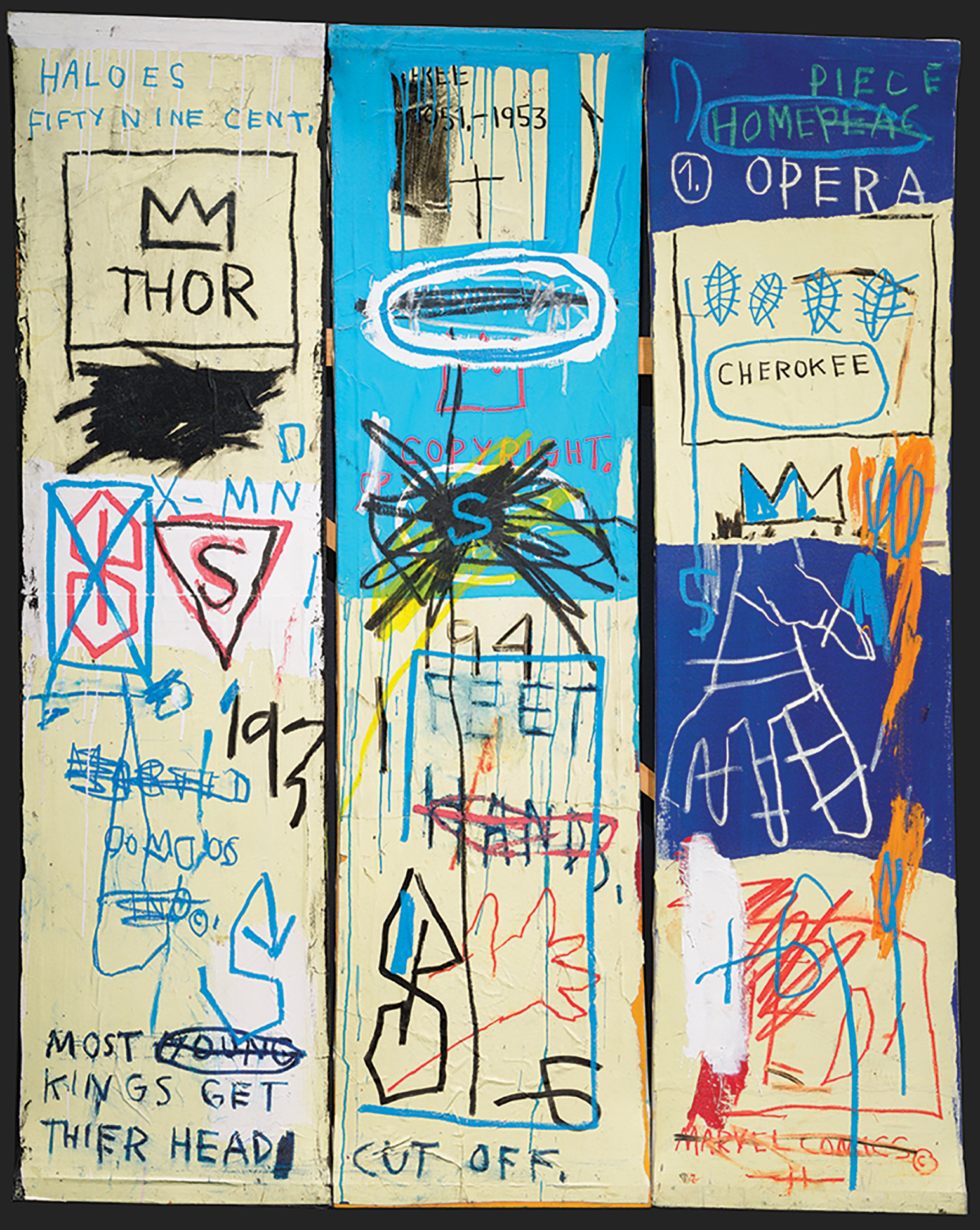

He did create at least two formal paintings while in Maui: “Rusting Red Car in Kuau,” and “Cash Crop.” Both were painted during Basquiat’s first trip to Hana, in 1984, and reveal the artist at the height of his transition into Neo Expressionism; prior to that, in the late seventies, Basquiat was best known as half of the graffiti duo SAMO, an abbreviation of “same old shit.” “Rusting Red Car in Kuau” builds upon a motif that appears frequently throughout Basquiat’s work: an automobile. Critics have suggested that this recurring image is an allusion to the trauma Basquiat endured when he was hit by a car as child, which resulted in a month-long stay at the hospital. The motif has also been interpreted as an image in conversation with his close friend Andy Warhol’s car-crash series from the sixties

Basquiat made visits to the small remote town on the eastern edge of Maui—a seeming refuge from the pressures of having catapulted to the red-hot center of the New York art world

“Cash Crop” feels like more of a departure for Basquiat, spacious in ways that contradict his sensibilities as a maximalist. Its rich reddish browns are unusually earthy, backed by a baby blue sky and the shaggy green stalks of a sugar cane plant. In the foreground floats a black box labeled “sugar”— a critique of colonialism via the sugar cane plantations that connected places like Haiti, where Basquiat’s father was from, and Hawai‘i.

Basquiat spoke to Cappadona about the racism he experienced in New York as someone perceived as an “urban threat,” and though Maui was seen as an escape from that prejudice, it was a fantasy that couldn’t hold. Cappadona recalls a couple of incidents in Hana when Basquiat was called racial slurs, eventually dampening his relationship to Maui.

Cappadona did eventually learn about Basquiat’s career, but it wasn’t until 2000 or 2001, more than 12 years after the artist had died. He was at the library, flipping through an old issue of Art in America when he came across a full-page ad featuring Basquiat and Warhol. Astonished, he went down a rabbit hole of books and movies about the artist’s life, the content of which confused Cappadona. So little about Basquiat’s persona as a rebellious and debauched genius didn’t square with the Jean-Michel that Cappadona knew in Hana—his friend, the “kind-hearted goofball.”

“I now tell people that I never knew Basquiat,” Cappadona writes. “I knew Jean-Michel. There is a big difference.”