Text and Images by IJfke Ridgley

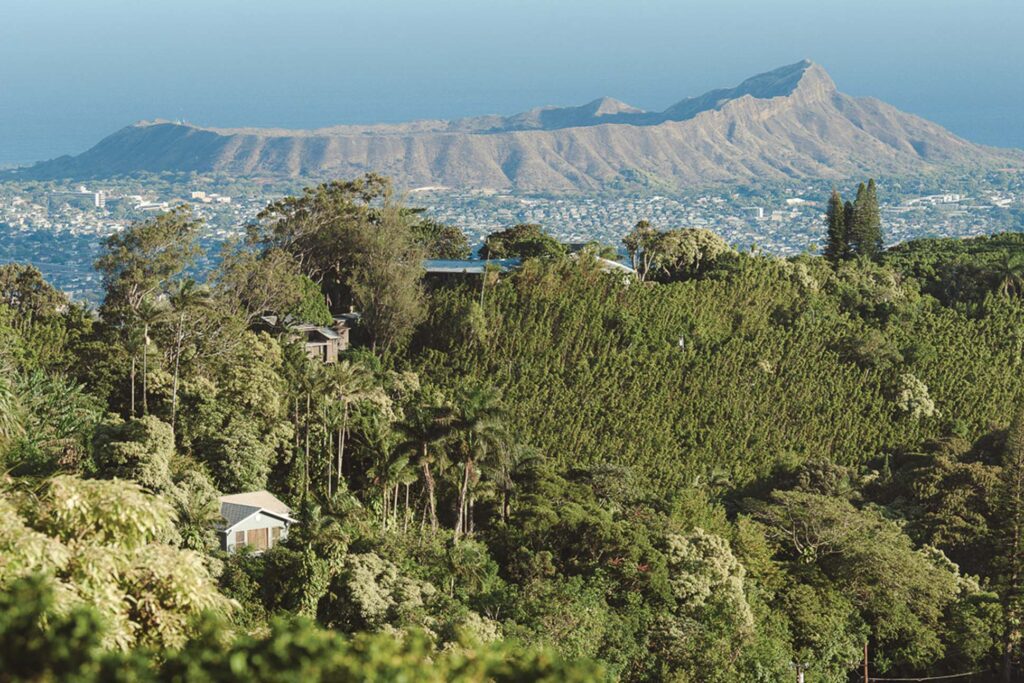

Despite its location just minutes from the urban density of Honolulu, the stretch of the Ko‘olau range known as Tantalus somehow seems to inhabit a world of its own. As one ascends along its windy road, the air noticeably cools; at night, a dense fog descends down through the trees. As hikers and mountain bikers and daytrippers make their way home, wary of traversing its hairpin turns in the dark, Tantalus is left for those who live there.

Interior designer Ginger Lunt is one such resident. Though much of her family—Mormons from Utah who settled in Hawai‘i in the 1850s—has called La‘ie home for generations, Lunt’s parents bought and relocated to a property on the upper reaches of Tantalus Drive when she was 12 years old. “I’ve always had a soft spot for the mountain and being surrounded by the forest,” she says. “All of its sounds, layers of green, and scents of flowers and eucalyptus.” For Lunt, Tantalus remains a calming oasis away from the crowded concrete jungle of Honolulu.

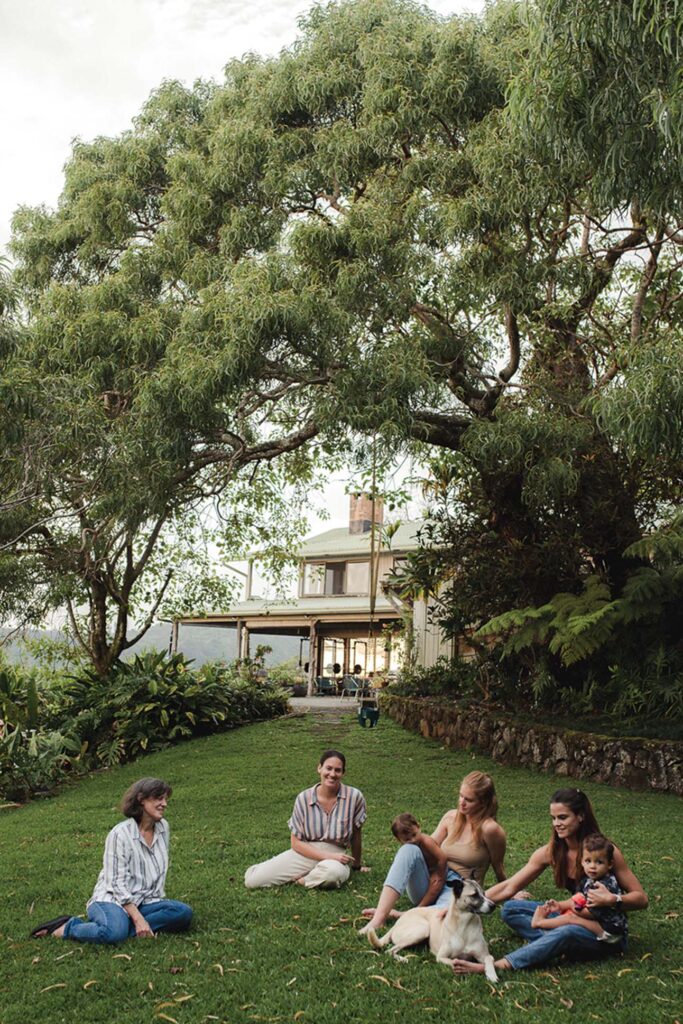

Today, Lunt lives in a property just two houses down from her childhood home. It also serves as headquarters of her interior design firm, Tantalus Studio, lovingly named after the mountain on which it resides. Behind a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it wooden gate camouflaged by foliage, the two-story house stands with simple bones and an open, welcoming façade that was originally designed in 1954. Thin support beams uphold a wrap-around lanai, framing an original lava-rock chimney and poured-concrete entryway. Inside, koa wood floors, board-and-batten paneling, and built-in millwork were lovingly restored to their original glory in 2018 by Lunt and a team of local craftsmen. “It has a lot of classic 20th-century Hawai‘i design elements,” Lunt says. “Luckily almost all of the house was still original and had never been changed, which I love.”

Despite their shared appreciation for privacy, Tantalus residents maintain a strong sense of community.

Lunt’s collection of artwork and furnishings are minimalist yet eclectic, offering a taste of Hawai‘i through the ages: vintage cane sofas, lauhala mats, a midcentury-modern dining set, contemporary Hawaiian art. The outdoor brick patio overlooking Pearl Harbor issurrounded by vegetation that turns from green to gold in the setting sun.

I follow Lunt up the rock pathway behind the house, through a dense thicket of bamboo, to the neighboring Potter residence. The Potters were the first family we interviewed in a now-years-long quest to tell the stories of Tantalus before some of its longtime residents are no longer here to do so themselves. Lunt asked me to photograph the many remarkable houses on the mountain, and the equally remarkable characters who reside in them, in hopes of compiling them all into a book.

“My passion for architecture and design, paired with my connection to the Tantalus community and deep love for this forest, is what inspired me to work on this project,” Lunt says. “There is such an authentic quality to the people and the homes that are up on this hill. There are homes built humbly and lovingly by their owners alongside homes created by well-known architects, all deeply inspired by the surrounding natural environs in different ways.”

Tucked into the forest and hidden from view, unique properties abound: humble wooden cabins that date back more than 100 years, Asian-inspired dwellings, and midcentury-modern marvels, including ones designed by famed Honolulu architect Vladimir Ossipoff. There are manicured estates too, like the sprawling property perched on the top of Round Top Drive, whose owners can still be found tending to its acres of landscaping and “flossing” the surrounding bamboo forest late into their Golden Years.

Many Tantalus residents have been there for generations. In the late 19th century, families sought out the area to build modest mountain cottages as second homes, going without electricity and running water for months at a time in the summer. Back then, Tantalus Drive was just a dirt road, and the trek up the hill by horse was arduous; a stop at the little grocery store that once stood half-way up the mountain supplied ice and basic groceries.

These days, the neighborhood continues to attract a specific breed. “It’s people who relish this kind of distance,” says Gary Gill, a former longtime resident whose family still calls the mountain home. “And you’ve got to be willing to put up with the wet and the mosquitoes and the fog blowing through your house, and your closet getting moldy in the winter.”

Resident Kim Coffee-Isaak echoes the sentiment. The active Tantalus Community Association member says the drive up the mountain is often polarizing for visitors. “When they get out of their car, they say, ‘Oh my god, that drive is so cool. It’s so beautiful. We just love it up here.’ Or, they get out of their car and say, ‘Oh my god, how do you do that drive every day?’”

Over the years, the mountainside enclave has been home to artists and intellectuals, architects and hermits—a down-to-earth bunch with a mutual appetite for nature and serenity. But as it turns out, a neighborhood defined by its mystery and isolation also tends to attract people who value their privacy, making the book project a challenging undertaking.

Thankfully, having grown up on the mountain, Lunt is friendly with the many families she passes on her evening walks on the hill. Some, she’s known since childhood. In her company, old-timers open up about childhood memories of their own, like sliding down the steep hills on ti leaves and the firecracker battles between gangs of Tantalus kids who claimed the forest as their own. Former resident Joan White fondly recalls a set of stairs at the bottom of the mountain, where, for decades, neighborhood children could sit and wait for a ride up the hill from anyone with a Tantalus sticker on their car.

There were also the “great guava wars.” “When we were kids, we would colonize a guava tree somewhere and then sort of make a village in it,” Gill remembers. When the fruits ripened, he and his friends would pick guava and haul them home in gallon-sized Folgers Coffee cans to his mother, the neighborhood’s de facto jelly maker. “My mom would spend the week making guava jelly and pass it around the neighborhood,” Gill says. “The whole valley smelled of guava jelly.”

Despite their shared appreciation for privacy, Tantalus residents maintain a strong sense of community. “They’ll really watch out for you,” White says. “They’ll help you out.” These are the stories of the community that Lunt and I hope to capture, from the mundane evening walks and chitchat about about the deplorable state of the road, to the neighborhood holiday celebrations and remarkable moments of aiding another in peril. In peering into the hidden homes on the hill, we aim to shine a light on the lives lived within their walls.