Text by Timothy A. Schuler

Images by John Hook & Skye Yonamine

They reveal themselves by their doors. Walking down the dead-end street, I count one, two, three, at least half a dozen, and there are likely more, since several of the entrances are hidden behind screens or obscured by thick vegetation. The houses, in various states of disrepair, are clustered together, their paint fading in the Pālolo sun. No two are alike. Some are low and wide, with delicate wood posts supporting the eaves. Others are tall, two-story things, boldly painted to accentuate their features. And yet all of the houses share one particular detail: a door with a long, narrow window running down its center.

This door detail is one of the signatures of Alfred Preis, the Vienna-born architect who designed dozens of buildings throughout Hawai‘i between the 1940s and 1960s and frequently collaborated with his better-known contemporary Vladimir Ossipoff. When he arrived in Honolulu in 1939, having fled Europe, he was given a job at the design firm Dahl and Conrad. Preis stamped his signature on his very first house, built in 1940 on Nāhua Street in Waikīkī—a door with a fenestration just a few inches wide, a gash of glass. He used it again for houses in Mānoa and Makiki Heights, and again in central Pālolo Valley for a long-forgotten project called Veterans Village.

Veterans Village was an affordable-housing development initiated in the aftermath of World War II. It comprised 86 single-family homes on 14 acres on either side of Pālolo Stream. All were designed by Preis, who after the war—during which he was briefly interned at Sand Island in Honolulu alongside fellow Austrians, Germans, and Japanese residents—left Dahl and Conrad and opened up his own office in Honolulu. The price of homes in Veterans Village began at just $7,500 (or $75,400 in today’s dollars). Nearly 70 years later, many of the houses still stand.

Today, Preis is best remembered as the architect of the USS Arizona Memorial, that iconic vessel that floats ghostlike over the sunken battleship in Pearl Harbor, but he spent a great deal of his career designing modest projects on modest budgets. He was concerned with progressive issues like the labor movement and fought to improve the quality of the built environment. “Preis’ clients were, for the most part, locals,” says Laura McGuire, an architectural historian and coauthor of a forthcoming biography on Preis. “He tended more toward a desire to make a kind of Hawaiian modernism for the people.”

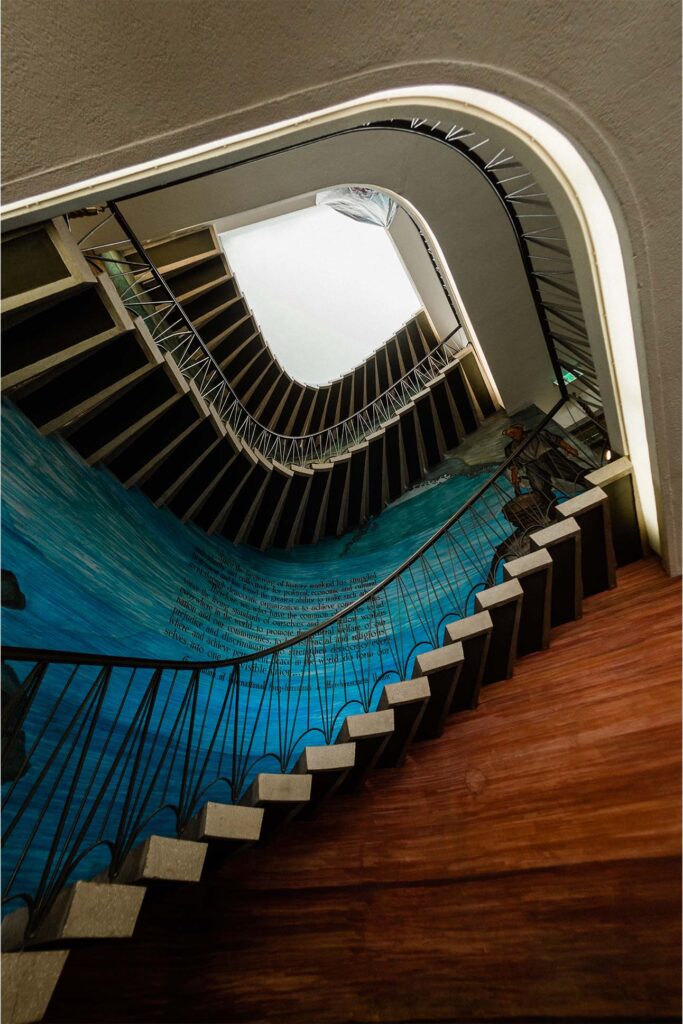

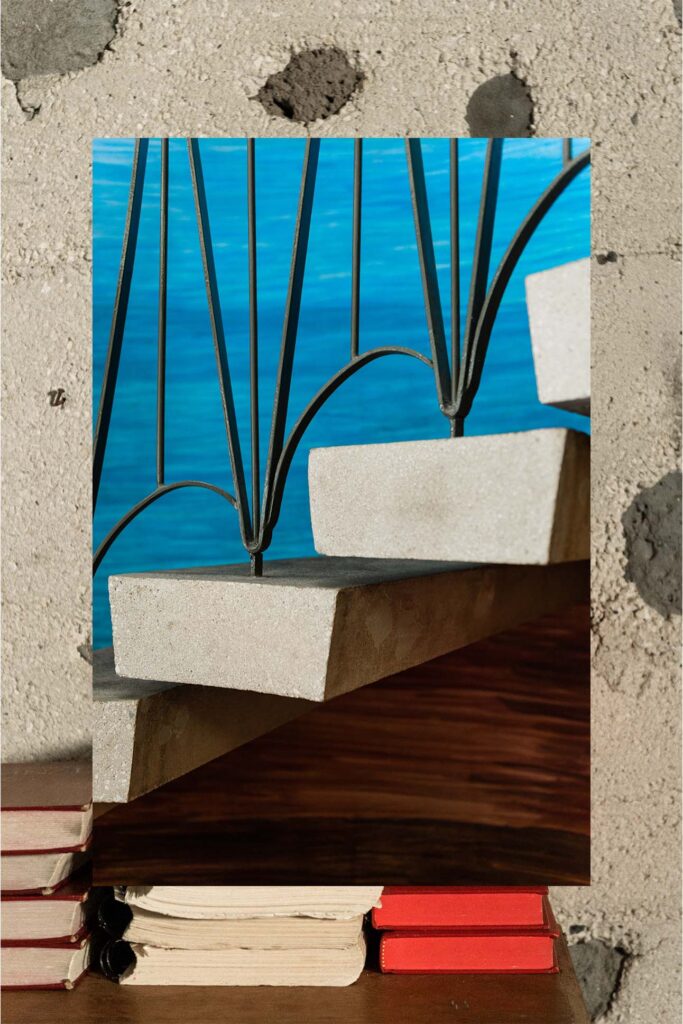

Among Preis’ earliest projects was the Labor Canteen, a cafeteria and event space for members of local labor unions, which was located at the corner of Kalākaua Avenue and Beretania Street. He also designed buildings in Hilo, Līhu‘e, and Honolulu for the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, the last of which features a dramatic, cantilevered stair and a three-story mural by Pablo O’Higgins, who was part of the Mexican mural movement and an associate of Diego Rivera. The slightly bowed building, located on Atkinson Drive and built in 1952, was both of its time and ahead of it, with a coffee shop and a rooftop garden alongside the dormitories for laborers.

Preis’ politics were informed by his childhood. He grew up in a working-class neighborhood, the eldest son of a Jewish family that had converted to Catholicism. He came of age in the Austrian capital during the 1920s, a period in which the socialist government funded the construction of more than 60,000 units of public housing, when the city was known as “Red Vienna.” Preis fled the country just months after the Nazis annexed Austria, narrowly escaping the horrors of the Holocaust, which claimed the lives of both his parents.

If Vienna instilled in Preis a deep-seated belief in the merits of socialism, it also inspired a lifelong passion for the arts. He loved the theater. His earliest aspiration was to become an actor, and before architecture, he had considered a career in stage design. This fascination with art is apparent in Preis’ work, not only in his attention to detail and love of bright and contrasting colors, but also in the way he made provisions for art in even the most modest of projects. Along with the house on Nāhua, for instance, Preis designed an eight-unit apartment building on the same property that included built-in frames he filled with prints by the artist John Kelly. “That was his thing. He was committed to art in architecture,” says Jack Gillmar, a retired schoolteacher and another of the forthcoming biography’s coauthors.

Gillmar should know. He grew up in the house on Nāhua Street, a modern, two-story box with a rounded plaster facade. Inside, it was full of custom details, including carved wooden drawer pulls and a mahogany staircase. In 1974, Gillmar and his wife, Janet, who is an architect, sold the property but decided to keep the house. They dismantled the structure piece by piece, labeling every tread, cabinet, railing, and door. They sawed the sandstone fireplace out of the wall. They took the staircase, the built-in bookshelves, the chrome bars that symbolically divided the living area from the dining.

They trucked everything to the back of Pālolo Valley and put the house back together, enclosing its orphaned interior in a new, more contemporary shell. It took the couple 15 years. When it was finished, they invited Preis and his wife, Jana, to lunch at the reconstructed house. “He was astounded,” Jack Gillmar recalls. “He was astounded that we saved it, that we put it back together, and he was even grooving on some of his own details. It was like his first child.”

Gillmar remembers Alfred Preis as a quiet, self-effacing person. “He never made a big deal about himself or what he contributed,” Gillmar says. “But in terms of architecture, he contributed a great deal.” Yet Preis’ legacy lay less in individual buildings and more in his advocacy for the value of good design. He championed the preservation of Hawai‘i’s natural beauty and chaired multiple committees dedicated to the protection of places like Diamond Head. In 1963, Preis became Hawai‘i’s first-ever statewide planning coordinator, bringing aesthetic considerations to bear on large-scale infrastructure projects such as Queen Ka‘ahumanu Highway on Hawai‘i Island and the Pali Lookout on O‘ahu.In 1965, Preis helped found the Hawai‘i State Foundation for Culture and the Arts, for which he served as executive director until 1980. It was because of Preis that Hawai‘i became the first state in the nation with a statewide “perfect for art” law, which earmarks 1 percent of all state construction spending for the commission or purchase of public art. During his tenure, Preis oversaw the purchase of more than 2,000 original works of art, including pieces by renowned artists such as Satoru Abe and Barbara Hepworth. Many remain on public display.

In this way, Preis had an outsize impact on Hawai‘i’s built environment. It also closed the circle. Preis had dreamed of being an artist, and he never lost faith in the notion that art and architecture could improve lives. Studying the homes at Veterans Village, each one with its own unique details, the craftsmanship is almost shocking. That an architect would put so much thought and care into low-income housing was—and remains—a radical act. But that was Preis. For him, architecture was a public good, not a luxury. “He was extremely hard-working, extremely dedicated,” Gillmar says of the man. “He was willing to give his all for the people.”