Text by Diane Ako

Images by John Hook

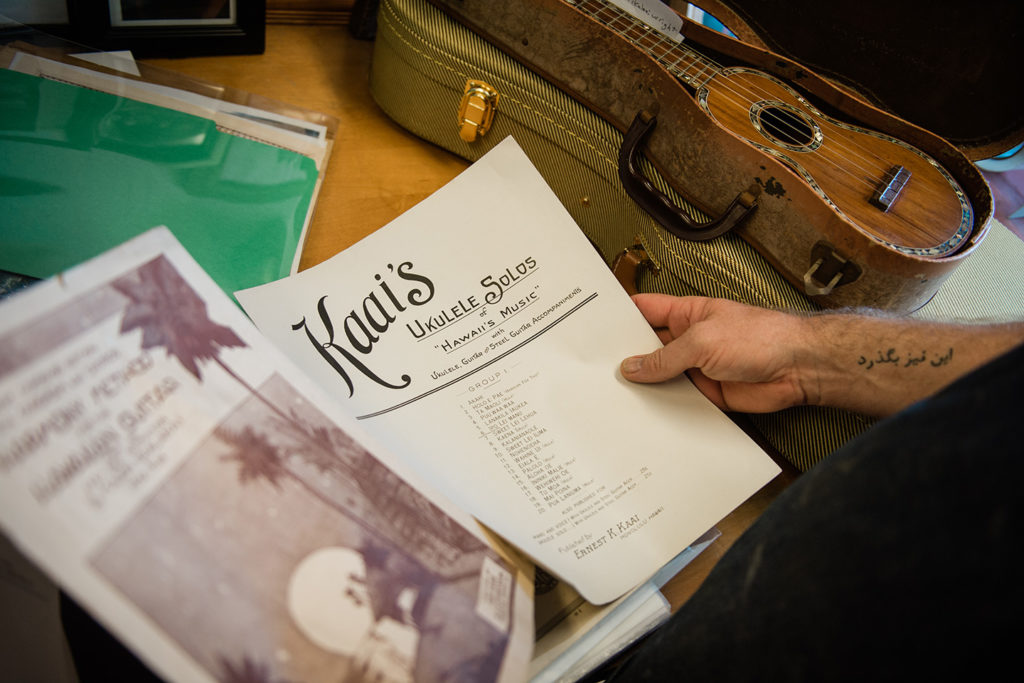

In a bright, cramped workspace in Kailua, Kilin Reece takes me time traveling. The 44-year-old luthier is surrounded by wood and string instruments of all types—flattop acoustic guitars, ‘ukulele, archtop guitars, and mandolins. Many of them are vintage. Some hang from the walls or rest on counters. Others sit in their cases on the floor. All of them await Reece’s attention.

“Think of all the history here,” he says. “These old instruments were loyal partners in music-making for years, to people who were farmers, plumbers, maybe even kings and queens. They are a witness to history.”

Now, those instruments, which he calls “kūpuna of wood and wire,” have arrived at his shop for tune-ups. Reece owns KR Strings, a stringed-instrument restoration shop. He knows how to build new instruments, but over the years, he found his calling to preserve older pieces.

Reece thinks of them less as musical instruments and more as living entities.

“I’m lucky to have spent hours peering into old instruments,” he says. “I’ve found love letters, set lists, locks of hair, lyrics, in either the instrument itself or the case. I like to think about who made the instrument, and where in the world it went with its owner. People say, ‘If this old guitar could talk.’ But they do! We just need to listen with our ears and our hands.”

I pick up the instrument nearest to me, an ‘ukulele, and ask what it says to Reece. He caresses it with his rough hands, then answers, “It’s from the 1890s. It’s got elaborate mother-of-pearl inlay, so it’s not cheap. It was handmade.” He fingers a small crack on the face and explains that it’s here to get the fracture fixed.

“What it really tells, though, is a story of humanity,” he continues. “Music is the common ground that transcends race, culture, and class.”

“If you’re going to entertain, you want to maximize your fun as the host, because your guests come to see you.” He recommends choosing a menu that you can prepare 50 to 75 percent of ahead of time. That way, when guests arrive, “Yeah you have to do your thing, but then you also have time to enjoy it.”

An avid researcher of the instruments that arrive at his shop, Reece, who is also a professional bluegrass musician, has developed an ear for the history of his craft. While researching one of his instruments, he realized that Hawai‘i has had a huge, and thus far uncredited, influence on modern music.

To explain what he means, he grabs a blonde-colored guitar and strums a few soft, soulful bars.

“Do you recognize that?” he asks with anticipation.

It’s “Blackbird” by the Beatles, whose rock tunes permeate geography and time. Paul McCartney crafted it on a Martin dreadnought guitar; John Lennon owned one of those guitars, too.

Reece then points out that the influential English band’s music had an unexpected Hawaiian influence. “This is a dreadnought guitar that I played it on, which is the most popular acoustic guitar in the world,” he says, drawing out the suspense. “Even if people don’t know guitar types, everyone’s probably heard music produced on a dreadnought.” The dreadnought’s ancestor, he shares, was a model called the Kealakai, made for a Hawaiian musician about 100 years ago.

He had this epiphany after delving into the origins of his own beloved dreadnought guitar. Its origins, Reece found, start in 1867 in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i with the birth of Mekia Kealakai, a boy who became a world-class musician. According to biographers, Kealakai skipped school so often that his parents sent him to the Reformatory School of Honolulu when he was 12 years old. That school had a band led by Henry Berger, more famously remembered as the Royal Hawaiian Band conductor.

In 1883, Berger took the reform school band to San Francisco to compete—the first trip abroad for the Royal Hawaiian Band. Kealakai was there as a 15-year-old reform school graduate. They introduced the world to a completely new sound: glee club songs of the Hawaiian Kingdom on ‘ukulele, mandolin, banjo, and guitar. It was a musical style developed in Hawai‘i in the 1870s, and Reece cites newspapers of the time, like the San Francisco Chronicle, raving about the concert using words like “new, novel, unprecedented, and exciting.”

For the following 10 years, Kealakai worked as a professional Royal Hawaiian Band musician. Then he toured the United States and Europe for the better part of the next 15 years, “spreading his music and pushing expectations of stringed instruments,” Reece says. In 1916, Kealakai asked Martin Guitar Co. to make him a new instrument: an extra-large jumbo steel-string guitar. He was the first person after which the company named a guitar model.

“The templates for the Kealakai were used to create the very popular dreadnought guitar,” Reece says, “which is the most popular acoustic guitar in the world.”

Reece’s growing fascination with turn-of-the-century Hawaiian string music took him to the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. There, he stumbled across a musical recording circa 1904 of a Hawaiian string band known as The Royal Hawaiian Troubadours and The Honolulu Students.

“This is probably the earliest recorded string band music in the world,” Reece claims.

Reminiscent of American folk music, the recording was made before the first popular wave of early country music, which began around the mid to late 1920s with the Carter Family and Jimmie Rogers’ earliest recording for Victor Records.

“Hawai‘i was not some isolated place that only received information,” Reece says. “It formed the soundscape, even in rural Kentucky, such that everyone was dreaming in Hawaiian music at that time.” Reece ticks off a list of the most iconic creators of popular Americana song tradition, like Jimmie Rogers, Bill Monroe, and “Mother” Maybelle Carter, all of whom he said grew up with Hawaiian string band repertoire.

Tunes many of us know and love, such as “Aloha ‘Oe” by Queen Lili‘uokalani, “Hawai‘i Pono‘ī” by King David Kalākaua, and “Hi‘ilawe” by Sam Li‘a Kalainaina, were written a century and a half ago. “Modern music owes much of its origin to Hawai‘i and these Hawaiian musicians,” Reece says. “It’s an incredibly vibrant and untold story, and the people who shaped that history are fascinating.” And it’s a piece of overlooked history he’s determined to bring to light.

In January 2019, Reece formed the nonprofit Kealakai Center for Pacific Strings, with the goal to “bring the backstory to the public.” He also co-organized a concert at St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Honolulu featuring an array of music from late 19th-century Hawai‘i. Local luminaries like Aaron Mahi, Puka Asing, Raiatea Helm, Starr Kalahiki, and Jeff Peterson enthralled a packed house. Reece took the stage as lead vocalist and guitarist to perform “Kentucky Waltz” accompanied by the Sovereign Strings Band.

The silky, earnest quality of his voice fell into place with the resonant sounds of the Hawaiian string band. “Kentucky Waltz” is a dead ringer for an earlier Hawaiian song “Pua Lilia,” and even in the first bars, I can hear both cultures beautifully synthesized in the ditty: the lonesome sound of bluegrass melding with the heartfelt strains of Hawaiian steel guitar.

The full weight of his pronouncements hit me as I sat in the audience listening to him. I fixated on each stringed instrument that sounded from the stage and remembered something Reece said about their inner voices: “We build a box, stretch strings across it, and invite magic to live inside.”