Text by Christine Hitt

Images by Dino Morrow

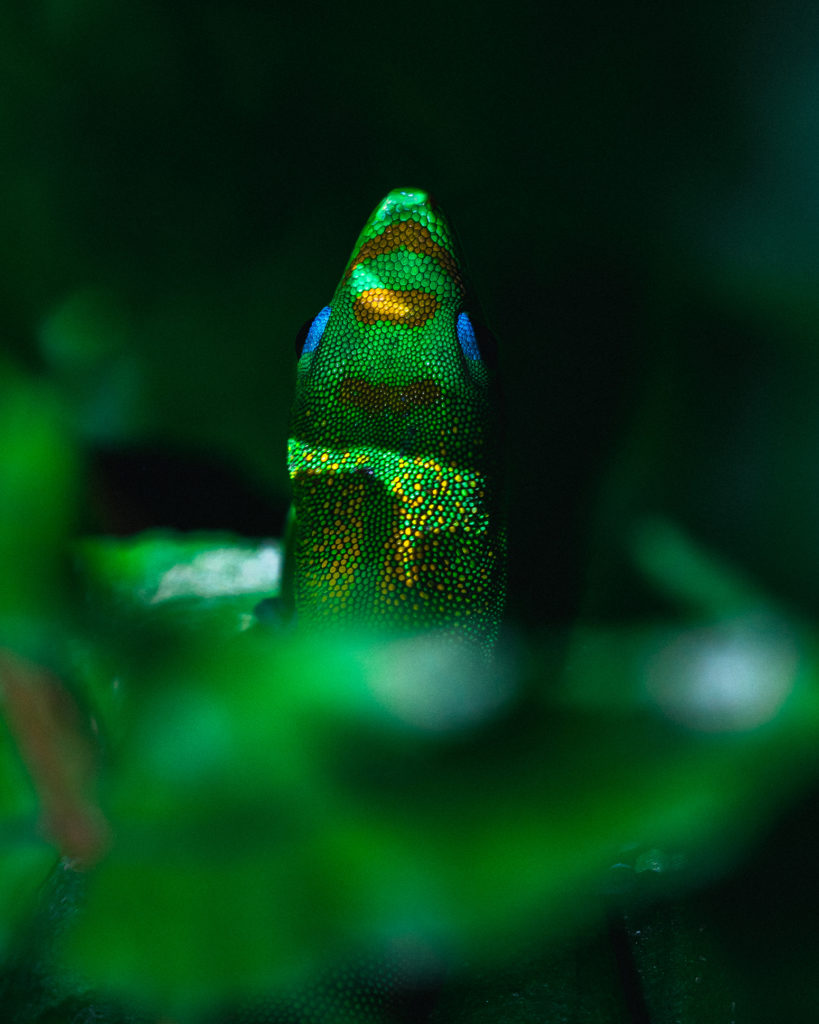

The dreaded mo‘o, or gigantic lizards, are the shapeshifters of Hawaiian legend. They are described as lizards, or a reptile of any kind and size that could be a dragon, a serpent, or a water spirit. Guardians of streams, waterfalls or lakes, they were most times female, and in some instances, take the form of a beautiful woman. An exception being Pana‘ewa, a reptile-man, who ruled the tropical forests of Hilo.

In one of the most famous legends of Hawai‘i, Hi‘iaka, the youngest sister of Pele, goddess of volcanoes, battled Pana‘ewa on her journey to Kaua‘i to fetch Lohi‘au, the man of Pele’s dreams. Hi‘iaka wanted to defeat mo‘o along the way as a way to help the maka‘āinana who feared them. When she arrived to the Hilo forest, Pana‘ewa blinded Hi‘iaka with his fog-arms, wrapped her in heavy mists, and shrouded her in freezing rain, until lightning storms were brought down on him and defeated him. As the story continues, Hi‘iaka would go on to meet other legendary mo‘o on the island of Hawai‘i, including Maka‘ukiu, a ferocious monster with a great mouth and strong tail; Pili and Noho, two dragons that look like logs in the Wailuku River near Hilo; and Mo‘olau, a dragon in Kohala with powerful jaws.

The mystery of the mo‘o lies in the fact that there are no native reptiles to the Hawaiian Islands, nor any bones of an extinct species to prove that one existed. The numerous species of geckos seen in Hawai‘i’s houses and backyards today are non-native and not the ones referred to in Hawaiian mythology. Nevertheless, legendary stories of mo‘o have passed down through generations and persist at water sources around communities across the Islands. Sometimes, they’re visualized through natural land formations, such as at Mo‘oula Falls in Moloka‘i’s Hālawa Valley, where rocks at the top of the waterfall look like the head of a giant lizard. Mokoli‘i, also known as Chinaman’s Hat, is said to be the tail of a giant lizard slayed by Hi‘iaka. And Molokini off Maui—another lizard head, cut off by Pele—are other examples.

Mo‘o are so deeply embedded in the culture that they’re even mentioned in Hawai‘i’s Kumulipo, A Hawaiian Creation Chant: The night gives birth to sluggish-moving mo‘o; Slippery is the night with sleek-skinned mo‘o. This means they’re already in existence at the time of Papa, earth mother, and Wākea, sky father.

Marques Marzan, Bishop Museum’s cultural advisor, explains that the legend of mo‘o were created from ancestral memories from when the Pacific people left the coast of Asia. It’s perhaps a memory of crocodiles and snakes from those ancient homelands.

“The idea and the story of mo‘o being connected to water and having these kind of reptile, lizard-like qualities stems from that ancestral memory of those places,” he says. “Those stories were so strong that they were able to persist all the way into the middle of the Pacific across generations of time. I think it’s that mythological story that is perpetuated through chants and songs and genealogies, but also that actual memory [of reptiles] that was able to persist that gets attached to those stories as well.”

Though feared, mo‘o were fierce guardians of water, which is a primary necessity for life. They weren’t just bad spirts; they protected those places, until death if they had to. In this way, the stories of mo‘o can be used as an environmental lesson.

“When we hear about mo‘o, there’s always that perception of fear that’s involved just because of the intensity and strength that these figures have in memory and stories and in all those different forms,” says Marzan. “I think that’s one of the takeaways that, for me anyway, they’ve represented that strength in caring for and preserving place, especially water. So to be this protector of water in that way, the giver of life where everything comes from, I think that’s a beautiful story.”