Text by Josh Tengan

Images by Mark Kushimi

Yvonne Cheng’s artistry in Honolulu has many chapters. The 79-year-old artist is known best for her large-scale paintings of Polynesian women, some that have been rendered into public mosaic murals across the islands and purchased for private collections. But her career is also full of surprises, with projects including stained glass for a chapel at the Grand Wailea resort on Maui, textiles for Kahala Sportswear, and interior design for a local CEO’s offices and private jet.

A working artist for more than 50 years, she still finds herself painting most mornings at her garden studio in Mānoa. When I join Cheng at her home on a Saturday morning to talk story, the moment feels privileged. Cool Mānoa breezes sweep through the yard as we converse over pastries and tea, looking back on a life rich in art and experience.

Born in Surabaya, East Java, in 1941, Cheng was raised in Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital. The 1940s were tumultuous, beginning with the Japanese occupation of the country during World War II. One of Cheng’s earlier childhood memories was being taken to an internment camp set up by the Japanese.

Following the war, Indonesia declared independence from the Dutch Empire, and after a bloody four-year revolution, it received formal independence from its colonizers in 1949.

After the war, Cheng spent her childhood and teenage years in Dutch schools, where she says her education was “very intense” and unsurprisingly Eurocentric.

“The crazy thing is that we had to learn the entire history of Holland, but we learned very little of Indonesian history,” says Cheng, who began studying art and drawing at a young age.

Her grasp of the human figure is no doubt partly due to close study of Dutch masters like Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Van Gogh. But it wasn’t until 1967, when Cheng and her then husband settled in Hawai‘i after a stint in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where they sought political refuge, that her art career began.

Upon moving to Honolulu, Cheng enrolled in a batik class at Bishop Museum. Batik, a textile tradition native to Java, is a part of Indonesia’s national dress and a tradition with which she was familiar.

Learning the labor-intensive wax-resist dyeing technique thousands of miles away from her homeland was a re-education of sorts.

Simultaneously, she became fascinated with Oceanic textiles found in the museum’s collections. Tapa, bark cloth typically made from wauke (the paper mulberry plant), is found throughout the Great Ocean.

In Sāmoa it is called siapo. In Tonga, ngatu. Fijians call it masi. In Hawai‘i, it is called kapa and was used for clothing, sleeping, religious ceremonies, and burial practices.

Cheng was struck by the intricate geometric designs and the delicate textured watermarks beaten into the cloth itself, a signature of the practice in Hawai‘i. In the late 1960s through the 1970s, the second Hawaiian Renaissance was growing, and kapa, considered a lost art form since the 1890s, was being rediscovered by artists like Malia Solomon, Puanani Van Dorpe, Marie McDonald, and Moana Eisele.

It was during the Renaissance that Cheng began to develop her own visual language. She celebrates the pattern work of tapa through the use of her native batik process. Stunning examples of her batik work can be found in the state’s Art in Public Places Collection and at the University of Hawai‘i Hamilton Library. She would work in batik through the 1980s before taking up painting on canvas as a less laborious process.

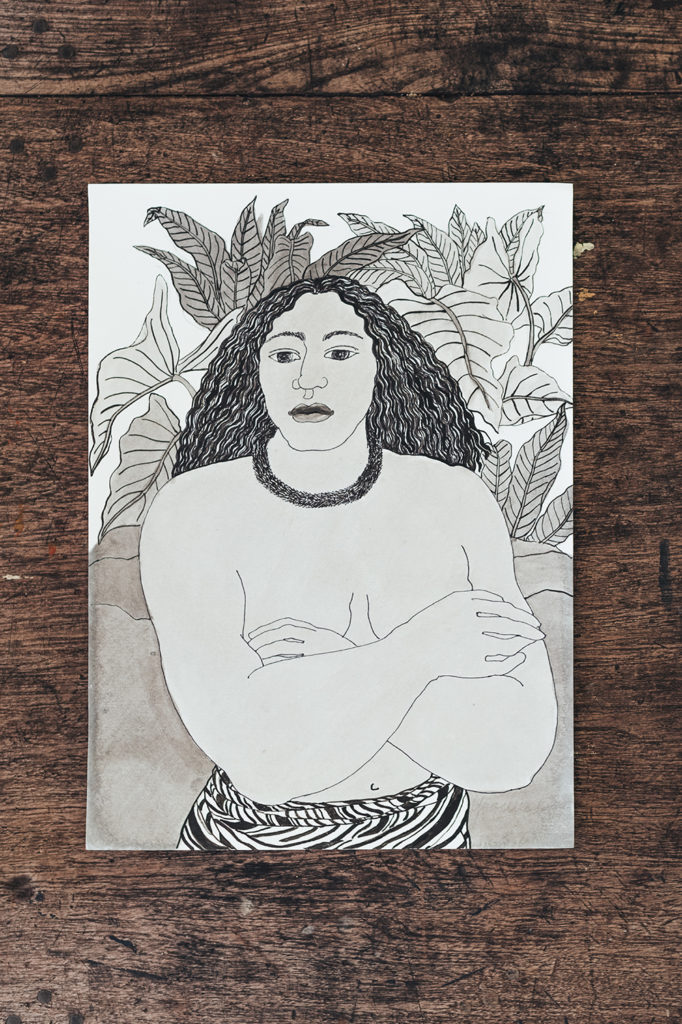

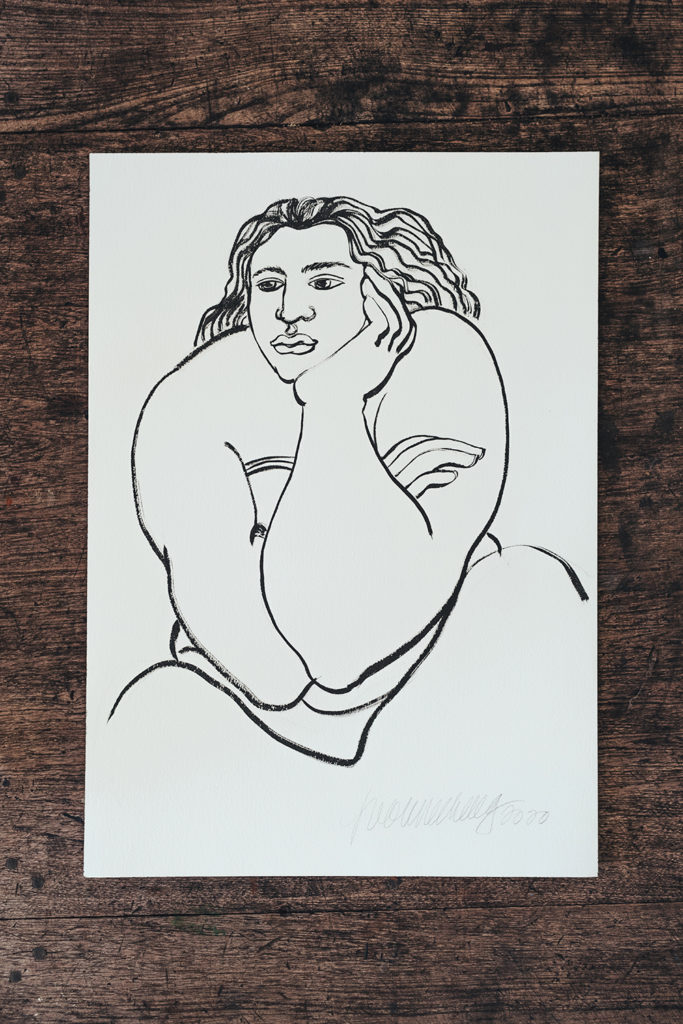

Till this day, Cheng’s compositions almost always feature Polynesian women of a bygone era, often draped in swaths of kapa, tied across their bodies into pā‘ū (skirts), kīhei (capes), and kīkepa (sarongs).

The geometric designs cascade over powerful brown bodies, larger than life, buoyant, floating on the surface of the work.

Like the akua wāhine of Hawaiian mythology, her figures exude a powerful sensuality, gracefulness, and dignity that is almost mystical, commanding the gaze of the viewer.

Currently, she is working on a new painting in her studio for an upcoming show. On the easel sits a square 4-by-4 canvas depicting a Hawaiian woman in traditional dress with the verdant Ko‘olau mountains as a backdrop.

Mauka from her yard is a similar view without a cloud in sight, nor regal woman, whose face and body she paints from her imagination.