Text by Spencer Kealamakia

Images by Chris Rohrer

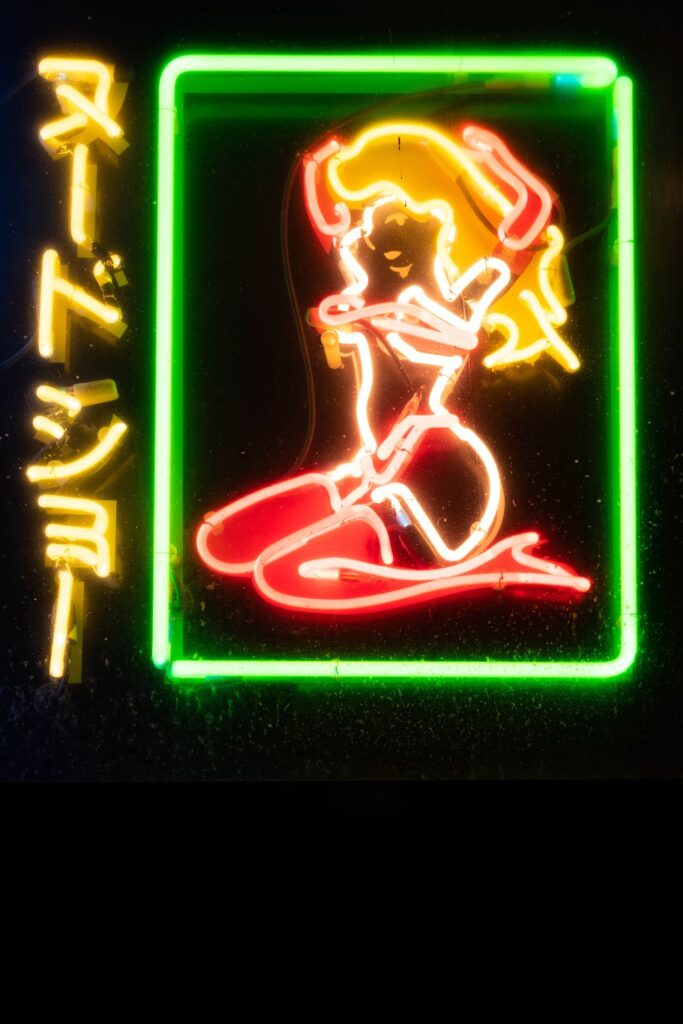

At night in Honolulu, neon signs invite us to satisfy our appetites. It’s the azure glow of “Leonard’s” that captures our senses before the scent of malasadas do. What ends with a late-night loco moco in a diner booth began under the spell of a Jetsonian sign and its electric green and red letters: Like Like Drive Inn. Oftentimes, a simple red and blue “Open” sign is more than enough to guide us in from the dark.

“Neon isn’t going anywhere,” says Von Monroe, a Honolulu sign maker. “Nothing can live up to that classic look.” He’s sitting at the work table in the center of Strictly Neon, his 500-square-foot shop, the last door in a Kalihi concrete walk-up that also houses a tattoo parlor, a jiu-jitsu studio, and a church.

Monroe has been in the Honolulu sign business since 1980, after the neon boom of earlier decades when neon lighting hung all over Waikīkī. When he began apprenticing in a sign shop, he learned everything there was to know about signs, except for neon. After failing to find someone in Hawai‘i with the know-how, he went to the continent to learn the craft. Then, he spent his after-work hours practicing making neon signs in his carport. Eventually it became intuitive, he says, “manipulating an instrument, eye-hand coordination.”

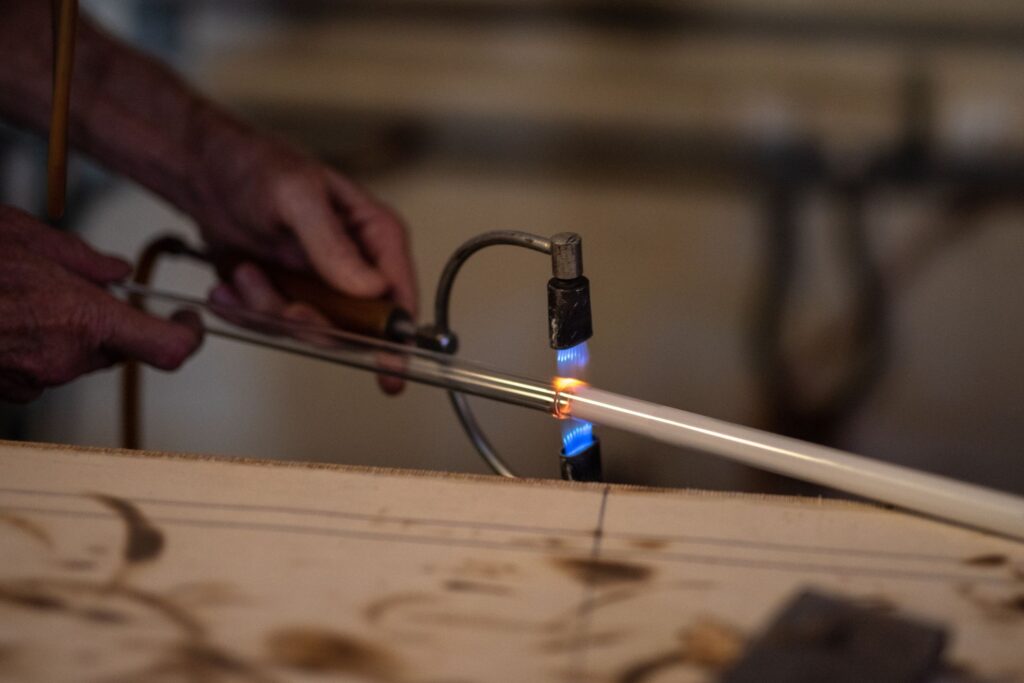

Neon-lighting technology and tools have remained largely unchanged since their creation and quick rise to popularity in France at the turn of the 20th century. Torches are still used to bend and shape the glass, and the neon light is still underpinned by the physics of an electric current running through pressurized noble gases.

“You got your fires,” Monroe says, pointing to a ribbon and a cross fire burner, each threaded onto a waist-high pipe stand. The ribbon burner puts out a thin, blade-like flame used to shape sweeping curves, especially for script typefaces. The crossfire consists of a pair of torches aimed at each other, and it is used to make more acute bends and to splice pieces together. The neon colors are produced by adding different gases or using colored, phosphor-coated glass. A dash of mercury bumps the luminosity.

Over the years, Monroe has watched signs go up and come down. Some have rusted away, and others have been resurrected. He knows the city by its show windows and marquees, a local history written in channel letters, depicted on fluorescent light boxes, and shaped in neon—a cacophony of silent pitches and come-ons.

He has his beloved neon signs around town, many of which he’s worked on. His favorites include the Hawaii Theatre sign and marquee, the nonfunctioning McCully Chop Suey sign, and the pink Pig and the Lady sign. He grieves the demolition of the Fisherman’s Wharf restaurant but finds relief in knowing the free-standing fish sign was saved. The iconic, complex Club Hubba Hubba sign on Hotel Street in Chinatown is another favorite of Monroe’s which took him eight months to restore.

But the one Monroe gets most excited about is the white neon star that goes up on the First Hawaiian Bank building each holiday season. “They have to crank it up by hand,” he says. He pulls out his phone and swipes to a photo showing a pair of men leaning into a winch crank, then to a photo showing the glass and stainless-steel star almost upright 20 feet from the rooftop. “I had the whole thing sitting right here,” Monroe says, his eyes darting around the studio as he recalls the space it took up. Though only lit up for a month at the end of each year, the sign rises above all others. It cuts into the night and seduces us the way all neon does, even if it’s only to stop and look.