Text by Jade Snow

Images by Chris Rohrer

The home studio of Native Hawaiian artist Solomon Enos is an unassuming trove of wonders. An Oculus virtual reality headset is nestled amid paint cans splattered in earthy hues. A hardcover copy of The Epic Tale of Hiʻiakaikapoliopele (his breathtaking illustration of the eponymous goddess on its cover) is sandwiched on a congested shelf, its load suspended precariously above the board game Warhammer and a crate of handmade sculptures. An army of tiny figurines stands en masse atop the shelf, where a moʻo (lizard) creeps among vines growing through the wood. “I am as organized as a forest,” he laughs.

Fittingly, nature is where Enos’ story begins. Growing up, Enos was immersed in a sense of kuleana (responsibility) to the ‘āina (land) through the work of his father, Eric, a talented Hawaiian artist who founded the nonprofit Ka‘ala Cultural Learning Center in Wai‘anae Valley in 1978.

There, the Enos family welcomed volunteers, often troubled by addiction and broken homes, and worked tirelessly to restore the valley and heal their community. In caring for the land and teaching valuable resource management, they also passed on Hawaiian knowledge in the process.

Though his spirit remained connected to the ‘āina, Enos’ imagination wandered. “My brothers wanted to do things outside growing up, but I wanted to go inside,” Enos says, gesturing to himself. He had a natural talent for art in his youth, which caught the attention of close family and friends. He recalls the advice of Uncle Eddie Kaʻanāʻanā, a beloved Kaʻala partner and famed kalo farmer, who took notice of the boy’s earliest works. While up in the mountains one day, when Enos was about 12 years old, Uncle Eddie pulled him aside.

“He took my hand, closed his eyes for maybe 15 seconds,” Enos remembers, “and said, ʻSolomon, if you’re given a gift and you don’t share it, it’s going to make you sick.”

That profound statement stayed with him ever since and has guided his lifelong practice of art and activism.

Enos finds endless inspiration in the juxtaposition of opposites—tradition and technology, urban and rural, Kū and Hina. His work, which explores Indigenous perspectives in the context of the modern world, seeks lessons within these dichotomies.

“The most important technology we have is compassion,” he declares, a theme woven throughout his art, most notably his mind-bending series Polyfantastica, a body of work that depicts an expansive universe he’s been developing over the last 15 years (think the science fiction of Star Wars, with the heart and soul of Avatar).

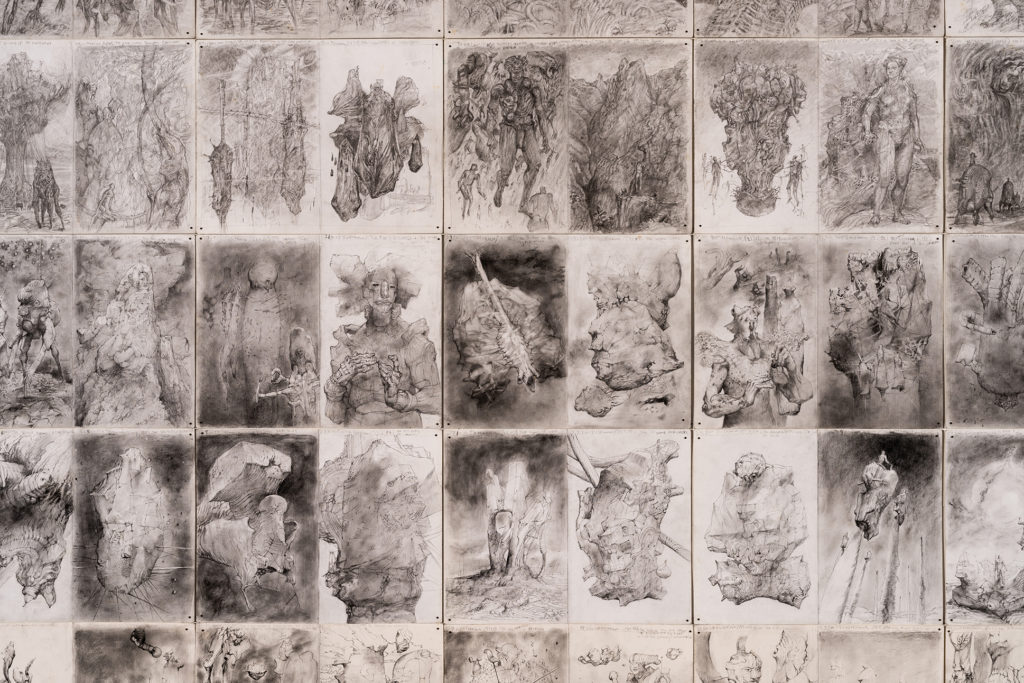

A visual thought experiment, Polyfantastica contemplates a simple question that piqued Enos’ curiosity more than a decade ago: What would it be like if Hawaiʻi had never been interrupted by Western contact? To date, the project includes 400 drawings of futuristic beings, artifacts, and technologies chronicled over an imagined 40,000-year timeline divided by four thematic epochs—Wa Kuu, Wa Rono, Wa Tane, and Wa Tanaroa—each based on a Hawaiian akua (god) and their defining characteristics.

Enos is meticulous in his illustrations, which include animalic warriors and “walking landscapes”—natural environments shaped into massive humanoids. He combines elements of flora and fauna into reimagined life forms with dynamic features, abilities, even built-in defense mechanisms.

“I think of [Polyfantastica] as activist escapism, or escapist activism,” Enos explains, turning one of his 40 handcrafted epoxy figures upright on a nearby table.

Fantastical and impressively detailed, they are among the many creatures that populate the world of Polyfantastica.

“They are basically kaona (hidden meanings) for how kūpuna (ancestors) thought of themselves,” Enos says. “They don’t just start at their poʻo (head) and end at their feet. They are the sky, they are the land, they are the mountains and oceans that surround them. For them, when you see someone doing hewa (wrong), you feel it. It’s an extrapolation of that very idea, but I’m telling it through the lens of science fiction.”

War and conflict hold our attention, but so can profound beauty and mystery.

Solomon Enos

Polyfantastica’s conceit is so audacious and nebulous it could fuel any number of iterations in film, animation, and virtual reality, all mediums in which his exciting cultural multiverse could thrive and evolve. For now, though, the ideas are still a work in progress, a universe unfolding in the numerous sketchbooks and miniature sculptures he’s made over the years.

Enos insists that today’s clickbait culture calls for a renewed emphasis on peace and compassion.

“War and conflict hold our attention,” he says, “but so can profound beauty and mystery.” Polyfantastica, then, is an invitation to contemplate “how humans and the natural world can be rewoven around narratives of harmony and hope.”

It’s a place to engage deeply with one’s imagination. In the realm of Polyfantastica, philosophy, creativity, people, and nature are one.

For details on viewing Solomon Enos’ latest work in-person visit capitolmodern.org/artists/solomon-enos