Text by Diane Ako

Images by John Hook

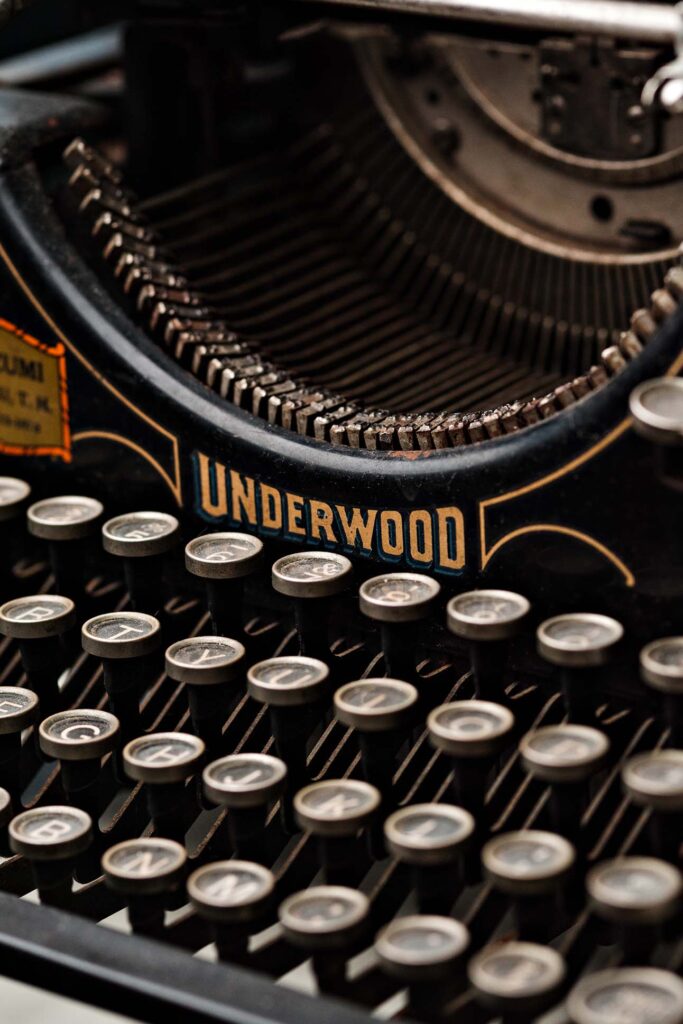

Compared to computers, typewriters are not efficient writing tools, but what they do offer is a welcome break from the high-speed digital age. The film California Typewriter, a documentary of celebrities who expound their loyalty to this machine, suggests as much. Featured in it is author Richard Polt’s “The Typewriter Manifesto,” which asserts: “We choose the real over representation, the physical over the digital, the durable over the unsustainable, the self-sufficient over the efficient.”

When Joshua Wisch, executive director of American Civil Liberties Union of Hawai‘i, saw the film and the famous typewriter aficionados it profiled, he was inspired to build his own collection. His personal inventory of vintage typewriters now numbers 12, which he keeps at his Kailua home. On a Sunday morning, he excitedly shows them off to me. He used one of them to write to actor Tom Hanks, who is featured in California Typewriter, to ask for a recommendation for a beginner’s typewriter. Unsure if he’d get an answer, Wisch went ahead and purchased a coal-black Royal Quiet De Luxe.

He sets it on the table. It’s a practical-looking machine that appeared on the market in the late 1930s. We feed paper into the carriage so I can test it. Its metal body has a sturdy quality, and its round keys are surprisingly resistant. The Royal makes me earn every word I type. I can understand why Ernest Hemingway was drawn to this model for producing his classic, minimalist prose.

Eventually, Wisch tells me, Hanks did respond to his letter, suggesting he buy any Sterling model of Smith-Corona. Hanks also recommended a pre-1960s Hermes (a 2000, 3000, Baby, or Rocket model) and an Ambassador—“if you have desk space,” Hanks wrote. So Wisch kept collecting.

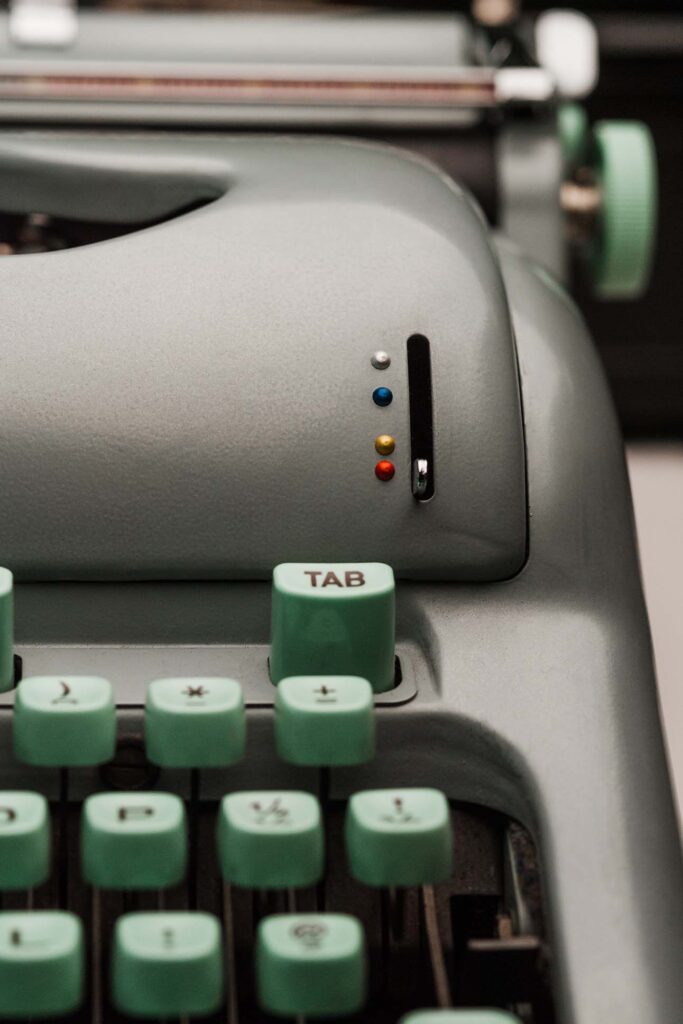

“I bought this beauty in Bremerton, when I was visiting my father-in-law,” he says, pointing to a Hermes 3000. The pretty little device has soft lines, a seafoam-green body and keys, and a curved silver carriage and return bar. “Look at the brilliant engineering!” he gushes about the typewriter’s design: The bottom of the machine has a lip into which the case neatly clicks and locks. “Also, you can reverse the direction of the ribbon in case you’re running out of ink, and this keyboard includes an exclamation point.” Wisch also marvels over the Hermes 3000’s dual-ink ribbon and molded keys, which fit to one’s fingers. Striking one of these keys has a buttery-smooth feel, with tension soft enough that Wisch’s hands never ache from typing on them.

Then there is his ultra-portable Olympia Splendid 33, which Wisch calls a “performer”—a small package with a big feel. It’s boxy and tan, rather forgettable in aesthetic. But what it lacks in charisma it makes up for with clever design and a workhorse attitude. To keep the machine’s profile low, its German designers made the entire carriage lift up when one hits the shift key. It has a handy snap-on shell, which makes it easy for Wisch to take this typewriter on his frequent work trips. “After the meetings, I have sat in my hotel room and typed over a dozen thank you cards,” he says.

Wisch claims to not have a favorite among his collection, rather choosing which model to use based on his mood. I decide to experience this for myself by writing to Hanks and asking what his favorite typewriter is. I slide a notecard into the carriage of the Smith-Corona Silent. With some dismay, I find that I’m frustratingly slow. On a computer, I type 80 words per minute. But on the typewriter, if I type too fast, the typebars tangle, requiring me to gently flick them back into place. If I make a mistake, there is no correction ribbon, so have to I backspace and physically type an X over the error. I forgot to hit Shift, so I get an “8” instead of an apostrophe, causing “it’s” to read like this: “It8s.”

But by the end of the letter, rather than being frustrated, I’m surprised by how much thought I have put into this missive. It dawns on me that collectors who opt to use typewriters are seeking to enjoy the journey of writing rather than the destination. It’s about savoring the tactile sensations: the fingers striking keys, the staccato of typeslugs hitting the platen, the ding of the bell to indicate the end margin.

The designs vary from boxy desktop machines with bulbous metal bodies to sleek, angular plastic portables with pared-down features for travel. The results, however, are consistent. Through this medium, writing becomes a meditative exercise. “It’s slower, yes,” Wisch says, of using any typewriter. “Once I type anything, it’s there on the paper. I can’t take it back. But I like that it makes me think about what I’m going to say.”