Text by Martha Cheng

Images by John Hook

By 2019, Daniel Kinzer had been to more than 70 countries. In the year prior, he spent two weeks in Antarctica as part of a National Geographic teaching fellowship, and then for a week, he studied island ecology at Isla Espíritu Santo, just off the coast of Baja California Sur. He decided he wanted to explore O‘ahu next, his home since 2016.

“I wanted to really appreciate home in the ways that I was being invited to appreciate these other places,” he says.

So he walked. He walked 140 miles around the perimeter of O‘ahu for two weeks, setting off from his home in Makiki and heading west. He chose to walk during the Thanksgiving and Makahiki season, a Hawaiian festival honoring Lono, the god of agriculture, fertility, and peace. During ancient times, ali‘i had circumnavigated the islands collecting offerings for Lono and assessing the health of the land and people.

Gratitude wasn’t Kinzer’s only motivation. He also wanted to uncover what he calls the genius of places on O‘ahu.

“The genius of a place is in its ability to hold the tension between resilience and transformation in a way that is typically inclusive and generous,” he says. “The way everything is interconnected and fits together so elegantly, and how it adapts and evolves.”

Kinzer, previously the director at Punahou’s Luke Center for Public Service, had just finished a degree in biomimicry, the design of materials, structures, and systems that are modeled on biological entities and processes. He had also started working with Purple Mai‘a, an organization dedicated to youth educational programs that combine modern technology and Hawaiian cultural values. He learned about ‘ike kūpuna, ancestral Hawaiian knowledge, and was beginning to “think about culture and community as a technology,” or how past traditions could provide solutions for the present.

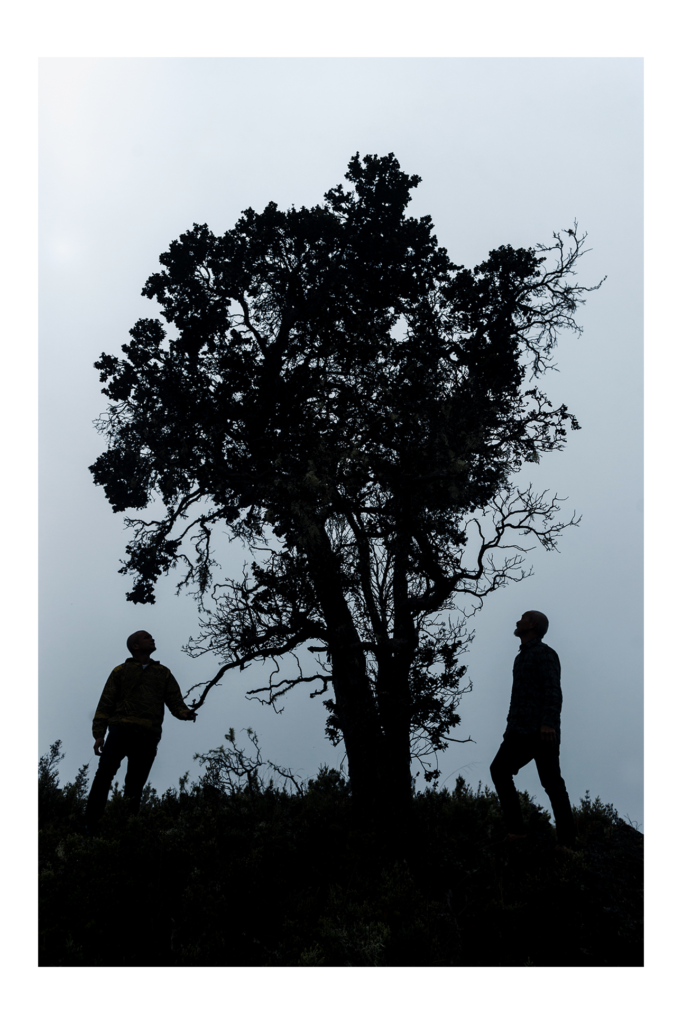

There are many ways to explore an island, but Kinzer chose to stick to the shoreline.

“There’s a lot of magic that happens in that intertidal zone,” he says. “This is a place where life is going to be born. It’s a nursery for sustaining our whole ocean.”

But what surprised him was the way the urban environment met the natural world along the shore. On the southern side of the island, he saw ‘ae‘o, the endangered Hawaiian stilt, in Paikō Lagoon in Kuli‘ou‘ou, and even along Pu‘uloa, or Pearl Harbor, and in small pockets of wetland right next to the power plant in Waipahu. On the leeward coast, he spotted monk seals huddled next to a houseless encampment at Mā‘ili Point, and near Wai‘anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center, he saw numerous hawksbill and green sea turtles where a few streams feed into the ocean.

He observed the rhythms of wildlife, the moon phases, and the tides. Laying down his sleeping bag on the beach at night, he had to consider tidal cycles to avoid waking up soaked by the incoming sea.

“So many of nature’s flows and rhythms have been disrupted or ignored that they’ve become irrelevant to people’s daily lives,” Kinzer says. “What if we could design our lifestyle and create a culture that was more in tune with them?”

As an example, he points to muliwai, where streams meet the sea and where salt water and fresh water mix, which were a central component in the design of loko i‘a (fishponds). Hawaiians built them on the shoreline and created ‘auwai kai (channels) to draw fish into the ponds.

It’s these sort of ancient technologies that Kinzer hopes to bring into the modern world.

He draws on the idea of an urban ahupua‘a, “the idea that the human-built environment

can serve ecological function and purpose, that it can be regenerative to both people and place, like the more land-based architecture of the Native Hawaiians.”

The genius of a place is in its ability to hold the tension between resilience and transformation in a way that is typically inclusive and generous.

Daniel Kinzer

Just before he set out on his first walk in 2019, he founded Pacific Blue Studios, which folds this philosophy and biomimicry principles into youth education as well as project design. Currently, he’s working with a team of youth to design, build, and install a sustainable moorings network in Hawai‘i, a project inspired by ECOncrete, an Israeli company that creates coastal infrastructure that works in concert with the sea. The company’s recent pilot project at the Port of San Diego features concrete structures that mimic natural tide pools, offering protection against flooding while encouraging marine life.

Kinzer has now made the around-the-island walk an annual ritual, hoping to find answers to modern-day problems by observing places where wilderness and civilization meet.

“We want to control everything, and yet life is uncontrollable,” Kinzer says. “Especially with climate change, we have to be ready to live an uncontrollable existence. We have to start thinking about how we design for the unknown. How do we design for constant change and fluctuations, how do we design for the ocean?”

“We used to think there was a separation between the old way of doing things and the new way of doing things,” Kinzer says. “But I think what we’re seeing emerge is an effective practice of looking at the so-called old way of doing things and translating it for today.” And Kinzer is one of the translators—the past and present technologies mixing within him, like fresh water and salt water on the shoreline.