Text and images by Martha Cheng

The medinas of Morocco smell of roses, orange-blossom water, and donkey manure. My two friends and I arrive in Fez past midnight. A taxi takes us through the wide, paved streets of the new town and then leaves us just outside the medina, the old walled city. Within, cars are not allowed, nor would they even be able to fit if they were.

Following our guide on foot, we slip past the walls and into a maze of darkness and silence. A left here, a right, a left … wait, was it a left? The narrow streets all look the same; the tightly packed, dun-colored buildings hem us in.

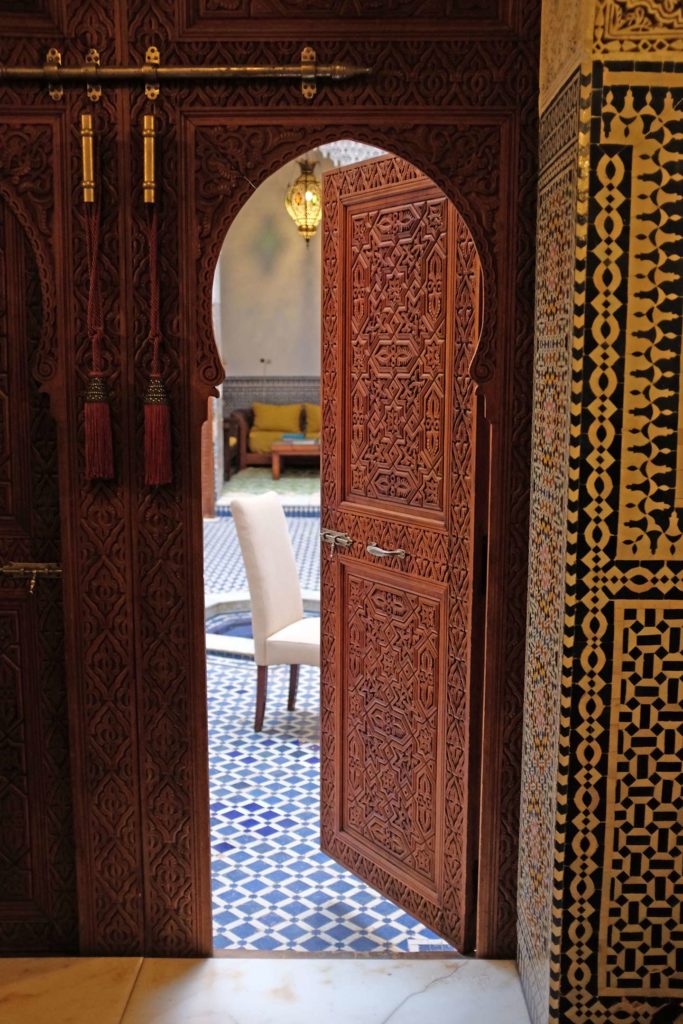

We pass through a wooden door in a dead-end alley, and suddenly, we are in a haven stretching three stories above us.

Tiles saturated with blues and greens pattern the floor and alcove walls, and the archways made of wood and stucco are carved as fine as lace. Coming from an absence of color and order, we have stepped into a burst of both.

To Morocco, apply Newton’s law of motion—for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction—and the country’s contrasts begin to make sense. The unpaved streets and alleyways of Fez’s medina zigzag as they please through rough, uneven buildings made of mud bricks.

But the arts, from the textiles to architecture, showcase patterns and tessellations of stunning intricacy and symmetry. When I step into a rug shop, I cannot stop pawing through the woven tapestries, until the shopkeeper has pulled so many there might be more heaped on the floor than are left on the shelves.

I feel greediness and sorrow that I cannot have them all, like Daisy sobbing into a pile of Gatsby’s beautiful shirts. During rush hour, I flatten myself along the walls to let donkeys pass. One is carrying animal hides, and the next, propane tanks.

I dart between people to chase a vendor wheeling a cart of dates, and another who is selling savory baked rice cakes dusted with cinnamon and sugar. In the souks, or markets, the people and sounds press up against me, the call to prayer over the loudspeakers adding to the din.

Then I enter our riad, a traditional house, and am enveloped in the quiet of its open courtyard, where a small fountain cools Morocco’s hot, dry air. Only a place so riotous could create such serenity.

Morocco possesses an entirely different culture, religion, and landscape than the place I live.

Like its tea, brewed so strong that its bitterness must be offset with blocks of sugar, this is a country of juxtapositions. I walk with women who cover themselves from head to toe, but in the public hammam, a bath house, we are all naked, save underpants.

A fleshy woman, full of softness, washes my hair and scrubs my body with soap made of eucalyptus and olive oil, pulls down my underwear, throws buckets of warm water at me. I have not been bathed by another since I was a baby.

This intimacy with a stranger astonishes me at first, but by the time she swaddles me in a towel, I am clean and comforted.

Morocco is the desert, an ocean of sand dunes, a landscape stripped bare. Morocco is the oasis that arises abruptly from starkness, where palms are heavy with ripening dates clustered like raindrops on branches after a storm.

One morning, we tiptoe into the Royal Mansour, a lavish palace hotel in Marrakech that was commissioned by King Mohammed VI.

The next day, we awake next to crumbling kasbahs in Agdz, on the road to the Sahara Desert. As we drive its bare embrace, we bring with us a box of sweets from Marrakech.

They are variations on figs and almonds and dates, some shaped into tiny roses of sheer and brittle pastry, sticky with honey, while others are crescents of soft and crumbling dough stuffed with almonds and cinnamon and perfumed with orange-blossom water.

By night, we are among the dunes, eating mutton tagine that our guide has cooked over the fire and bread he baked by burying it directly in the hot coals and sand.

I’m drawn to Morocco because of these contrasts, but perhaps the greatest contrast is between the life I know in Hawai‘i and the lives I see here.

Morocco possesses an entirely different culture, religion, and landscape than the place I live.

It even seems to occupy a different time, a time when objects are still made by hand, the rugs woven on the loom, the ceramics formed from and fired in the earth, the leather produced in an 11th century tannery using the same techniques as when it was founded.

The medinas confuse our GPS, rendering it useless; a lodge owner draws us a map with pencil and paper, a meandering line that sends us along an old caravan route to the desert, passing Tamegroute and other tiny towns that look as if they’re hewn from the cliffs, the mud-brick buildings the same ochre color as the dirt they stand on.

Many of these places are mostly abandoned, the people having left for more modern dwellings and towns.

But the old cities still stand, a reminder of where they once lived.