Text by John Wogan

Images by Mark Kushimi

Tucked into the valleys, ridgelines, and coastal enclaves of O‘ahu are some of the most quietly remarkable houses of the Pacific. These midcentury homes defined the residential architecture of the ’30s through ’70s and reimagined island living, blending modernist principles with an acute sensitivity to climate, topography, and local materials. They are also becoming increasingly rare. As newer builds crowd the island with sealed glass towers and air-conditioned convenience, a small but devoted group of homeowners are preserving the legacy of O‘ahu’s historic homes. They’re choosing not just to live in these spaces, but to restore and reimagine them with reverence.

Brian Lam knows better than most what that devotion looks like. The founder of the product recommendation service Wirecutter (which he sold to the New York Times in 2016) and a self-taught craftsperson, Lam spent five years restoring an Albert Ives-designed home tucked near Diamond Head with a motor court, courtyard, lānai, yard, and pool, all looking toward the ocean. “It was hell on earth,” Lam admits. “I didn’t go on vacation for four years. I wanted to quit all the time.” By the end of the renovation, though, he’d not only rebuilt the house, he had also reshaped his own life. In the half-decade since he acquired the home, he transformed from a novice admirer of woodwork to an apprentice in Japanese carpentry.

Lam’s approach to restoration was shaped by a deepening appreciation for both the structural intentions of Ives and the lineage of Japanese design that influenced Hawai‘i’s architectural language. The project also became a study in material limitations and craft traditions. “There isn’t anything too exotic in Ives’s homes—redwood, fir, a little koa,” Lam says. “But all owners of historic houses live in absolute terror of finding craftspeople sensitive enough to work on them as well as appropriate materials of high enough quality.” That anxiety—of loving a home but not knowing how to care for it—drove him to become a student of traditional methods. “I had zero woodworking experience [when I bought the house],” he says. “But I went to Japan to look at buildings with an architect who worked at a carpentry firm. Witnessing them craft the most beautiful wood joinery I had ever seen left an impression, and I finally picked up some tools two years later. By the end of the restoration project, I was able to help with some of the carpentry.”

For Lam, though, the desire to preserve an older home such as his extends beyond aesthetics. The best homes in Hawai‘i, he says, were designed for “the way we live in this corner of the world.” Often, older residences were built to be in harmony with the islands: floorplans harness the tradewinds, deep eaves shade from the encroaching sun, covered outdoor spaces extend living areas into the garden. As such, these historic houses are inherently more conducive to island living. The effect is particularly pronounced when compared to the “square boxes from Southern California architects we see these days,” Lam says. “What happens to these foolish designs when they are closed off from the breezes or it starts raining when the windows are left open on a house with no eaves?”

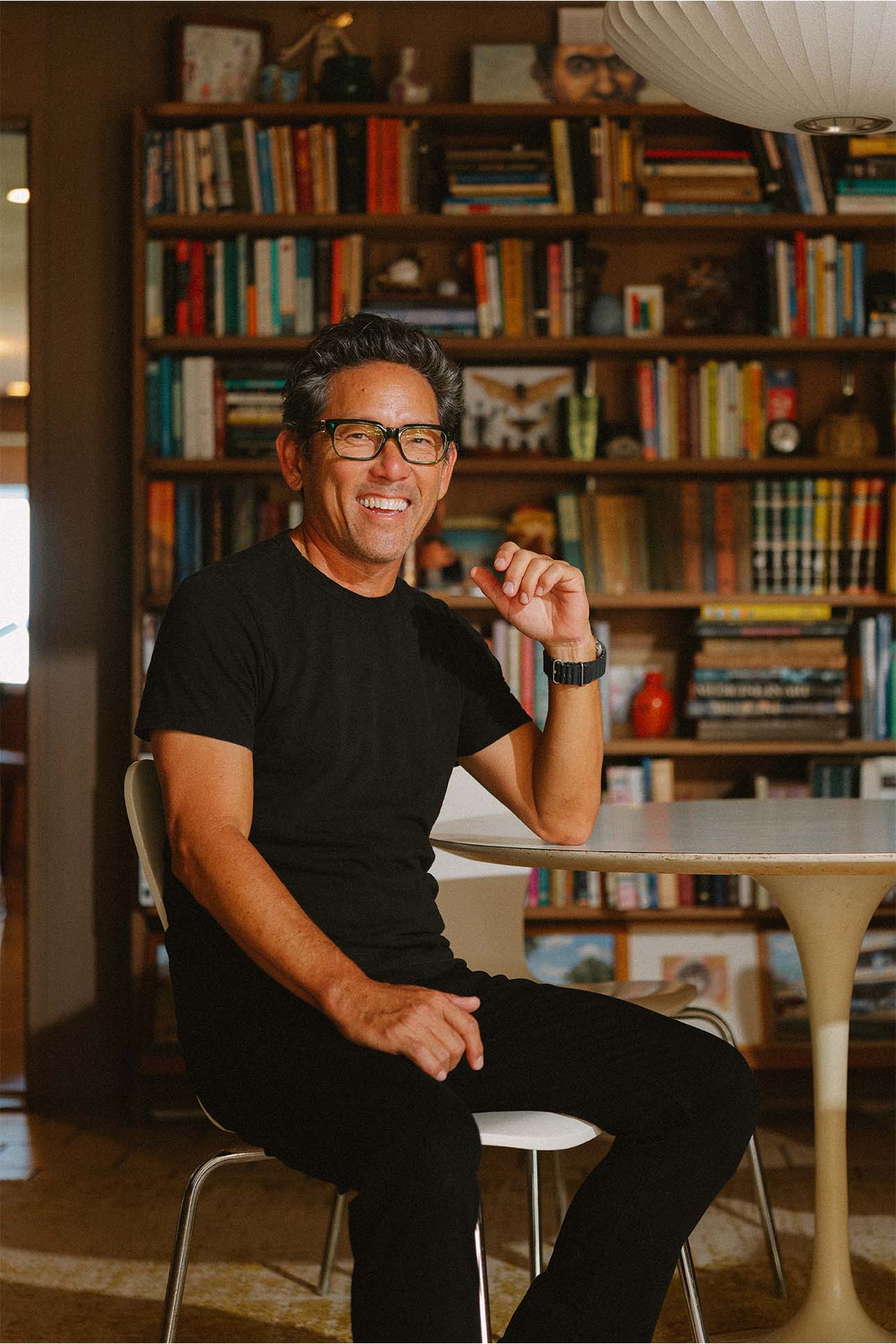

Across town, art advisor Kelly Sueda took a quieter, but no less intentional, approach to restoring his family home, which was designed in 1959 by Vladimir Ossipoff, the most celebrated architectural modernist in Hawai‘i. Sueda grew up steeped in midcentury design. His father was an architect who briefly worked with Ossipoff in the late ’60s. Inside their family home in Mānoa, Wasilly and Eames chairs and Saarinen tables were fixtures of daily life. So when Sueda and his wife stumbled across an unlisted Ossipoff property nestled behind a stand of trees, just eight houses from their own, the decision to buy was immediate. “The second I saw it, I called my wife and told her to wake up the kids from their nap and walk over,” he recalls. “Three weeks later, we owned it.”

The renovation was driven by a desire to update the home for modern living while staying true to Ossipoff’s principles, including an indoor-outdoor fluidity, deep connection to the landscape, and a restrained palette of natural materials. “We opened up the kitchen to the dining room and removed the shoji doors to the living room, which unlocked ocean and Diamond Head views from the heart of the home,” Sueda says. But nothing was changed without thought. Every redwood scrap was saved, repurposed, or matched. “One of the greatest compliments I received from an Ossipoff purist was asking if I had done anything to the home,” he says. “I really wanted it to feel like what could have been the original design.”

Sueda’s favorite details are the ones that serve both function and the story of the house. A coral tree once shaded the lānai, helping frame the angular structure in nature. When it fell in a storm, the loss felt personal, but Sueda soon found a replacement to keep the spirit of the original tree intact. Today, a juniper grows in its place. Ossipoff’s trio of fireplaces—traditional brick in the living room, a copper freestanding one in the den, and a rare hibachi-style fireplace—remain untouched. “We still use it when we barbecue with friends,” Sueda says of the kitchen hibachi. “It’s a unique double-sided hibachi that opens and closes from inside and outside the house. So if we’re entertaining or cooking steaks for family night, we can have charcoal-cooked barbecue from inside the kitchen. I love it.”

Twelve years after completing the renovation, Sueda still finds himself learning from Ossipoff. He once considered removing a wall to expand the living room view, until he realized they housed pocket doors. “When we experienced the first Kona windstorm, I understood why they were designed that way,” he says. “He cleverly placed all the venting windows east and west so the air could flow through the room but not endanger the interior from inclement weather. These kinds of things shaped my views on architecture.”

Architect Graham Hart, co-founder of Kokomo Studio, also understands the power of restraint. Along with his business partner, Brandon Large, Hart took on the renovation of a midcentury residence for homeowner clients Taea Takagi-Jones and Grant Jones in 2022, completing the project in 2024. Built along Tantalus, a winding neighborhood along the Ko‘olau’s slopes, the home was designed by Philip Fisk, another important but lesser-known architect from Hawai‘i’s postwar boom. Fisk’s homes were clean and clever, marked by fixed grids, honest geometry, and a precise logic in materials. Yet, time hadn’t been kind to the Forest Ridge bungalow. The kitchen had been haphazardly expanded, its layout confused by decades of ad hoc remodeling.

Hart’s job, as he saw it, was to subtract. “We didn’t add square footage and didn’t drastically change the location of rooms. Instead, we simplified and cleaned up the design,” he says. One challenge was structural. The kitchen had a load-bearing wall bisecting the space. Removing it required a new beam and an ‘ōhi‘a post to pick up the roof load, an elegant solution that now blends into the open plan. Another hurdle was material: The original redwood tongue-and-groove, tight-grain and unpainted, was irreplaceable. Most of the salvaged wood couldn’t be reused. Against the odds, the contractor found a local mill with a matching supply. After multiple finish tests, they achieved a tone that blended seamlessly with the old wood, and it could even be applied to new oak cabinetry. “Now that the kitchen is done and it’s opened up to the rest of the living space, it feels rightly situated as the center of the home for both school nights and entertaining,” Hart says. “It is a continuation of the rest of the house, and though all of it is new, it reads as old.”

The location also shaped the renovation. Tantalus is some degrees cooler than town, and it is one of the few places in Hawai‘i where a fireplace isn’t just ornamental. “These single-wall houses have no insulation, so it’s actually necessary,” Hart explains. Yet the home still had to manage solar heat gain, so they added horizontal fins to shade the southern facade, and swapped out windows for sliding glass doors to increase airflow. “Keeping the internal spaces open with minimal walls, and having as much permeability to the exterior walls, also helps in keeping the space naturally ventilated on those humid days in the mountains,” Hart says.

The throughline with each project is a shared ethic of care, a belief that these historic homes are more than relics. They are living systems, responsive to climate and culture, that only survive when inhabited with knowledge and humility. “If I were to build a new home now, I would utilize all the gifts Ossipoff gave us in this house,” Sueda says. “Intelligent design, I’ve learned, can also be aesthetically beautiful.”