Text by Lisa Yamada

At 73 inches tall and only 26 inches wide, “Rui Rui’s World II” is dreamlike in form, weighty yet ethereal. This 1,800-pound marble sculpture is stretched out of proportion, rendering it both mystifying and meditative. Like the many works for which its creator, renowned artist Jaume Plensa, has become known, facing the sculpture feels like encountering a sentient being from a future utopia.

The striking obelisk-like bust is the artist’s first work to be displayed in the islands, and it will find its home in Park Lane Ala Moana’s permanent art collection. Before its anticipated arrival in the islands, the sculpture toured the United States with Human Landscape, Plensa’s largest exhibition in the country.

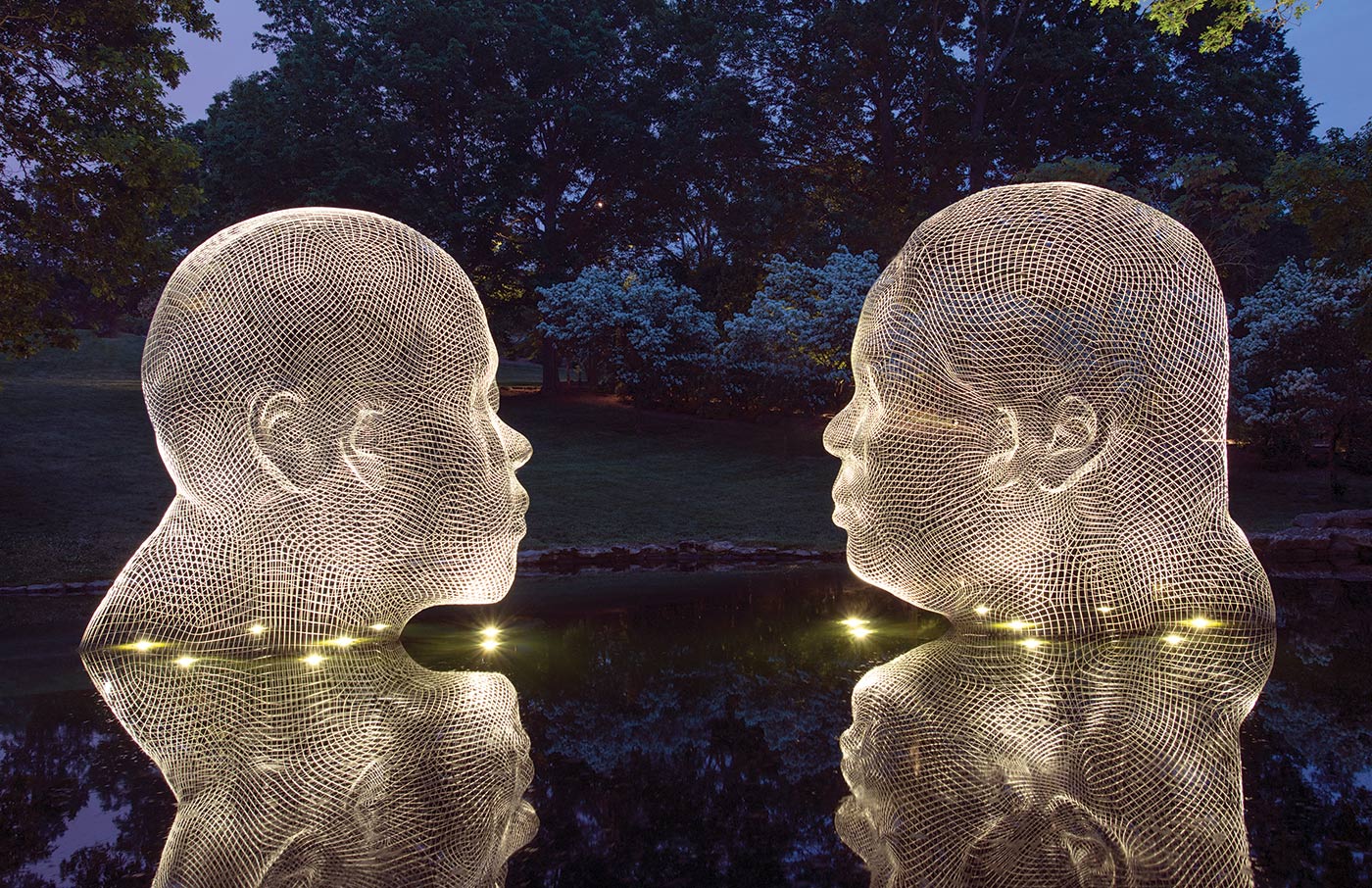

Accompanying “Rui Rui’s World II” in the Human Landscape exhibition were sculptures composed of metallic letters, text fragments, and poems welded together, creating “silent messengers containing fragments of past and future conversations,” as the Cheekwood Botanical Garden and Museum of Art in Nashville, Tennessee, described them.

While Plensa’s creations can be found in museums and private galleries around the world, over the years, the Spanish artist has been most celebrated for his large-scale work in public spheres—“Echo” in New York’s Madison Square Park, “Roots” in Tokyo’s Toranomon Hills, “Olhar Nos Meus Sonhos” (which translates to “To See My Dreams”) on Botafogo Beach in Rio de Janeiro. “He isn’t simply siting sculpture,” British curator Claire Lilley said of Plensa’s work during an interview with Bloomberg in 2015. “He’s creating situations where conversations take place.”

The artist works with mediums ranging from wood to bronze to stone to glass, and uses high-tech methods of creation and installation to transform notions of public space.

He’s creating situations where conversations take place.

Nowhere is this technique more evident than at Plensa’s Crown Fountain, set in the midst of Chicago’s Millennium Park. Since its debut in 2004, the fountain has become a play area for thousands of visitors, who romp through its reflecting pool during hot summer months and run beneath the two spouts of water that cascade from its rectangular glass towers.

Initially, there was some critique of Plensa’s use of LED lights to display various faces of 960 diverse residents—Chicago’s mayor was concerned it was “too Times Square for Millennium Park”—but today, the fountain has been warmly welcomed as part of the city.

Plensa has never shied away from incorporating such technology into his art. Kelly Sueda, the private arts consultant who secured “Rui Rui’s World II” for Park Lane, points to another of Plensa’s creations, this one crafted for the 2015 Venice Biennale, which featured two gigantic mesh forms that seemed to float slightly above the floor of the 400-year-old Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore.

“Jaume noted that when art was commissioned centuries ago, the work that was going in basilicas or cathedrals was contemporary,” Sueda says. “It wasn’t like they were going to bring in 200-year-old art.”

Since then, Plensa’s work has continued to weave a line connecting the past with the present. It’s why his sculptures resonate so strongly with viewers, including residents of St. Helens near Liverpool, England, where coal miners faced a bleak future when the town’s mines were closed after 400 years of operation.

Funded through the arts initiative, The Big Art Project, Plensa’s “Dream,” a 66-foot-tall, bright white figurehead, shone like a lamp in the darkness, bringing the townspeople, many of them burly coal workers, to tears.

Plensa will never forget the unveiling: “One of the miners tells me, ‘Jaume, when you are in the pit 300 meters deep, the darkness is so deep, light becomes a dream.’”