Text by Laura Pollacco

Images by Yuna Yagi and Andrew Faulk

Down a narrow, nondescript road not far from Yoyogi Park, the unassuming exterior of Ichijiku Gallery belies the treasures within. On first glance, you’d never guess that through the glass doors and up a flight of steps awaits a prized collection—not of gold or jewels, but of kimono fabric.

There are few cultural costumes more recognizable than Japan’s kimono. The garment has transcended its literal meaning, “thing to wear,” to become a revered form of iconography. Despite its enshrined significance, however, kimono culture is fading. Textile arts associated with the kimono, from the production of Ōshima-tsumugi, a fine Japanese silk, to the textile dyeing technique katazome, are in drastic decline, threatening the loss of thousands of years of crafting knowledge. The survival of these art forms may now depend on one thing: whether or not they can adapt.

Some may balk at the idea of changing something as traditional as the kimono, wishing instead to keep Japan’s cultural costume in stasis. Others, like Ichijiku’s founder, Aaron Mollin, know change is necessary to keep kimono craftsmanship alive.

Ichijiku began at a crossroads in Mollin’s life. At 34 years old, he left behind a career in law and was retracing his steps from his days as a college exchange student in Kyoto. “I had the opportunity to examine my life and think about what I wanted to do next,” Mollin says. He was in search of his ikigai, his sense of purpose—a future that could weave together his creativity and his admiration for Japan. Luckily, Mollin still had connections in the city, leading him to a serendipitous meeting with a former restaurateur from Kyoto’s Gion district.

The answer to Mollin’s search was quite literally laid out before him in the form of an extraordinary 30-piece kimono collection. Over the course of three hours, the restaurateur relayed every story and technique behind her vast collection of traditional garments before handing it all over to Mollin for the inconceivably low sum of 5,000 yen, approximately 50 dollars. For Mollin, it was a eureka moment. “Clearly, I had not shown kimono the requisite amount of attention. I had no idea just how incredible they were,” he says. If he, a long standing Japanophile, had overlooked the history and craftsmanship behind kimono, he was certain that others had too.

Simply reselling the garments wasn’t enough for Mollin. Instead, he was determined to create something new. He discovered a few instances of suits made from kimono, but he was baffled to find that they featured only the subdued tones characteristic of men’s kimono fabric. Nearly indistinguishable from a traditional wool suit, they preserved none of the kimono’s ornateness nor the intricate embroidery or dyeing visible on the women’s kimono he had procured. He decided then that Ichijiku would stand as a keeper of craftsmanship, creating bespoke apparel that exalts the beauty of one of Japan’s most iconic garments.

At first, Mollin was turned away by tailors in both Japan and his home country of Canada, all of whom were unwilling to deconstruct the garments, finding them cumbersome and unlikely to yield the right amount of fabric for a suit. Then, just as he was ready to give up, “when I believed it to be impossible,” he says, a fortuitous meeting with a Japanese tailor showed him a new path. He was advised to consider tanmono instead, the bolts of narrow-loomed cloth used to make kimono. “I realized that these kimono have a life before they become kimono, and it’s in the form of the fabric,” he says. A friend in the kimono industry provided him with a roll of tanmono produced by his company, one woven using a technique known as Nishijin-ori. “In addition to the fabric being symbolic of the strength of our friendship, it also provided me an opportunity to learn about how durable kimono fabrics could be—and that certain weaves, like Nishijin-ori, could be used for suiting,” he recalls. “From that roll, the first Ichijiku suit was born, and it was a thing of beauty.”

This process became the brand’s blueprint. Today, Ichijiku’s offerings are made almost entirely from women’s kimono and tanmono, transforming traditionally feminine garments and fabrics into suits and bomber jackets. That isn’t to say his brand is men’s only. Though the suit jacket is inherently more popular among men, Mollin has always thought of his brand as unisex. The common thread among his clientele is “a deep appreciation for art and fashion,” he says. “They want something unique, and they have no issue with standing out from the crowd—if anything, they prefer to.”

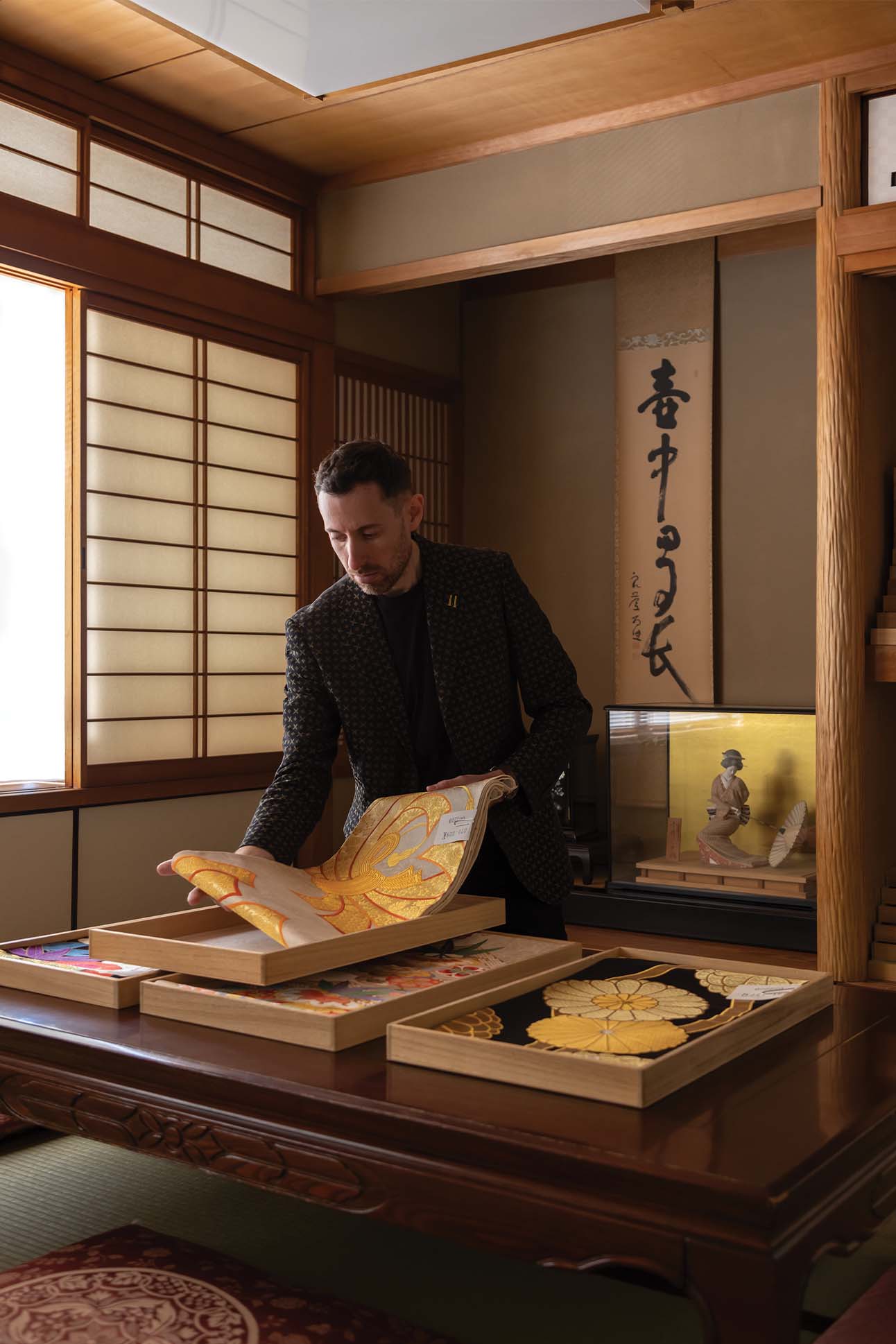

Ichijiku’s well-appointed showroom in Shibuya feels less like a store and more like a stylish living space—that is, until Mollin pulls back a large sliding door to reveal Ichijiku’s proverbial treasure chest. The store’s back wall is adorned with millions of dollars’ worth of tanmono, rolled, stacked, and ready for inspection. Alongside them are mannequins showcasing Ichijiku’s impeccably tailored suits.

“Every single tanmono here is one I have personally selected, that I have been immediately attracted to,” Mollin says. While sourcing, he prioritises fabric he’s never seen before, or regions and techniques new for the brand, in hopes of building “the most diverse collection of kimono fabric in the world.” Mollin takes immense pride in his understanding of the fabrics, discussing certain rolls with excitement and taking great care when handling the tanmono he has collected over the years.

“We don’t waste any fabric here. Even the smallest scraps we keep, and we create these pieces,” he says, gesturing to the scarf wrapped around his neck. Atop a base of red silk, scraps of leftover tanmono are stitched together with gold thread, a nod to kintsugi, another revered Japanese art form. The scarves function as “memories of past pieces that we’ve made,” Mollin says. “Every one of these was a roll of fabric we have turned into a jacket and given a new lease on life.”

Though sustainability is a pillar of the brand, Mollin knows that working exclusively with vintage fabric isn’t the most sustainable approach for ensuring the longevity of the industry itself. “If you’re just focusing on vintage fabrics, you’re not really supporting any of the existing fabric makers,” he says. Beyond sourcing vintage tanmono, Mollin has increasingly worked with established and emerging kimono fabric makers, forming relationships with artisans from Kyoto, Amami Ōshima, and other culturally significant regions.

Reminiscent of the Japanese concept of “unmei no akai ito”—the red thread of fate that connects two individuals who are destined to meet—an Ichijiku garment is a tangible link between its wearer and all who have had a hand in the garment’s creation. Entwining the past, present, and future of Japan’s textile culture, each piece is a wearable embodiment of everything Mollin is striving to achieve: an ode to traditional craftsmanship and a bid to ensure the continued survival of a cherished craft.