Text by Kylie Yamauchi

Images by John Hook

Saimin, Hawai‘i’s humble bowl of noodle soup, was kindled on the islands’ sugar plantations in an act of community building. As the origin story goes, at the turn of the 19th-century, plantation workers shared meals and ingredients from their respective ethnic backgrounds during lunchtime. Chow mein, ramen, and pancit ultimately produced the basis of the saimin dish: light wavy noodles in a dashi-based broth topped with Asian ingredients such as kamaboko, char siu, and wonton.

By the 1930s, the dish was a staple meal for plantation laborers of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, and Portuguese descent, even more so with the emergence of saimin stands that catered to them. Shiroma’s Saimin stand in Waipahu’s Japanese camp sold bowls for 5 to 10 cents.

In accordance with the laborers’ grueling 10-plus-hour shifts, Shiroma’s operated from 5:30 a.m. to 11 p.m daily. Stands also began to offer teriyaki beef sticks and hamburgers, which today remain popular accompaniments to saimin.

Considering the racial divisions and hierarchies that structured plantation living, the invention and early partaking of saimin can be read as acts of imperial resistance against white plantation owners and foremen, who enforced disunity among various ethnic groups to prevent unionization.

Many people outside of Hawai‘i are unfamiliar with saimin, but intimately acquainted with ramen, which had its own popularity boom in the 2000s. The difference between the noodle soups is minimal but distinct: Saimin noodles hold higher ash and egg content than ramen noodles, giving the former a chewier texture while keeping its thin shape.

Saimin broth is also typically clearer than that which accompanies ramen. While ramen is a favorite dish on the continental U.S. thanks to modern chefs such as David Chang, saimin remains Hawai‘i’s go-to noodle soup.

The word “saimin” is thought to be Cantonese (supposedly sai meaning thin and min meaning noodles). Despite its Chinese denotation, saimin is commonly associated with Japanese cuisine. Perhaps because, in the 1900s, many nisei (second generation Japanese) opened restaurants that specialized in saimin.

Some of these Japanese-founded restaurants still operate today, such as Forty Niner Restaurant, Shiro’s Saimin Haven, Sekiya’s Restaurant and Delicatessen, and Shige’s Saimin Stand. Even today’s largest family-run noodle manufacturer in the state, Sun Noodle, was founded by Japanese immigrant Hidehito Uki in 1981. With a single noodle machine and without a word of English, Uki perfected his recipe for saimin noodles using feedback from local restaurants.

One restaurant supplied by Sun Noodle is Palace Saimin, a 74-year-old institution in Kalihi. Founded by Kame Ige, an Okinawan immigrant, the hole-in-the wall gives off a modest yet intimate atmosphere.

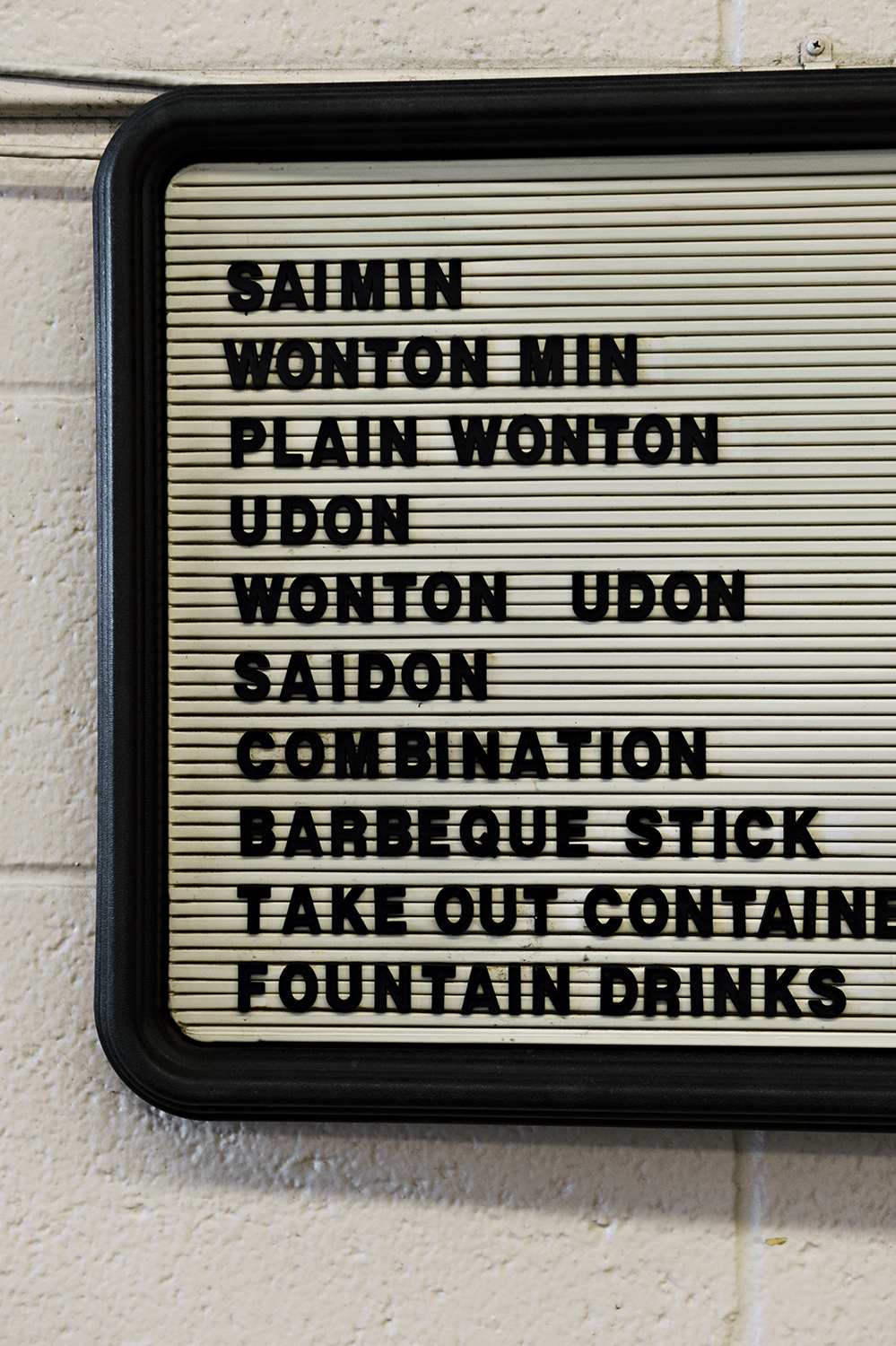

A Coca-Cola letter board on the wall advertises several menu items all under $10. In the morning, Setsuko Arakaki, chef and former owner and waitress of Palace, sits in the corner of the shop expertly folding wonton and preparing beef sticks for the day’s orders, while chattering in Japanese to regular customers.

“One characteristic that frequently makes our place special is the comfortable, informal conversation that stirs up between tables and customers that don’t even know each other,” says Scott Nakagawa, co-owner of Palace and Arakaki’s son-in-law. “We also frequently witness the kindness of our regulars treating first timers, many times leaving before the treated party even knows that their bill has been taken care of.”

The atmosphere in which one eats saimin is just as important as the dish itself. For chefs Chris Kajioka and Mark “Gooch” Noguchi, opening a saimin restaurant was about paying homage to the perennial dish and the eateries that came before them.

Before opening Papa Kurt’s in November 2020, the culinary friends talked with the owners of Palace, Shige’s, and Shiro’s to receive their blessing and invite them to visit their restaurant. Kajioka and Noguchi were adamant about having the menu, decor, and ingredients simple, as their late friend and restaurant’s namesake Kurt Hirabara would’ve wanted it. Although the chefs prioritize using fresh and local ingredients, Papa Kurt’s prices are affordable, keeping with the tradition of saimin shops.

“I think there’s a need for places that feed the community at a good price point that’s real food,” says Kajioka, who still enjoys a bowl of Zippy’s saimin like he did as a young chef.

Today, saimin continues to bring Hawai‘i’s families and friends together. Not much has changed from the original plantation dish, save a few new garnishes. Saimin’s simplicity, heartiness, and affordability is the reason for its continued popularity and ubiquity. But it’s legacy progresses for other reasons

“Saimin is our endemic dish,” Noguchi says. “It speaks volumes about who we are and where we came from. It’s like Israel Kamakawiwo’ole’s ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow.’ Saimin is always going to be timeless and it’ll always be there.”