Text by Eunica Escalante

In the wilds of Hawaiʻi, from the misty upcountry of Hāmākua to the lava-covered fields of Pāhoa, mother nature casts an imposing shadow.

The less inclined would find it an intimidating setting, but for architect Craig Steely, the islands’ dynamic topography is a welcome muse—a proclivity that revealed itself at the inception of his career. In 1998, the then-fledgling architect was contracted to design a home in the rugged lava fields of Puna on Hawaiʻi Island.

The resulting property was a sleek, futuristic structure in stark contrast to the acres of craggy aʻā flows that surrounded it.

The home was an early portent of his now signature site-specific philosophy, where a hyperlocal understanding of the islands’ land and history offers a fresh interpretation of the oft-referenced “Hawaiian sense of place.”

Part of what sets the 58-year-old architect apart is his departure from the stereotypes that have dominated Hawaiʻi’s visual identity for decades. To Steely, plantation-style homes and island motifs have been reduced to copies of copies that now function as symbols of exoticization rather than a true representation of Hawaiʻi’s current cultural landscape.

“I’m not Hawaiian, and I didn’t grow up in Hawaiʻi,” says Steely, who for the past 25 years has lived half of the year in the Hawaiʻi Island home he designed for his family. “That’s why I think it’s kind of appropriation if I just started copying these Hawaiian motifs,” Instead of succumbing to tropes, Steely draws inspiration from the land itself, designing homes with structures that are in conversation with their surrounding environment.

It’s an approach fostered by Steely’s childhood in the Sierra Nevada foothills, where his natural surroundings fueled a burgeoning understanding of the relationships between the built environment and natural landscape. “Some of my first architectural experiences were in the mountains, hiking around a river or rock formations,” he recalls.

With each home, Steely is building a new visual language for Hawaiʻi architecture, one that has already won him several accolades, most recently the Award of Excellence in the 2022 American Institute of Architects Honolulu Design Awards for his work on an off-grid residential project called the Musubi House. Situated amid acres of erstwhile pastureland on Hawai‘i Island, the squat concrete structure rises from the rolling hills as if chiseled out of the mountainside. Floor-to-ceiling glass windows comprise much of the façade, offering panoramic views of Mauna Kea on one end and the Hāmākua Coast on the other. A triangular opening in the center leaves a portion of the home exposed to the elements; when it downpours, as it often does in those high elevations, a curtain of precipitation falls into the atrium below—Steely’s version of bringing the outdoors in.

While his portfolio is mainly an ode to Hawaiʻi’s remote scenery, Steely has been looking to urban landscapes like Honolulu for an opportunity to flex a different sense of hyperlocality. “Every project is so site-specific,” he says. “I have an incredible love and respect for Hawaiʻi, and with each project that I do, I’m learning more about what Hawaiʻi really is.”

Invigorating ʻIke

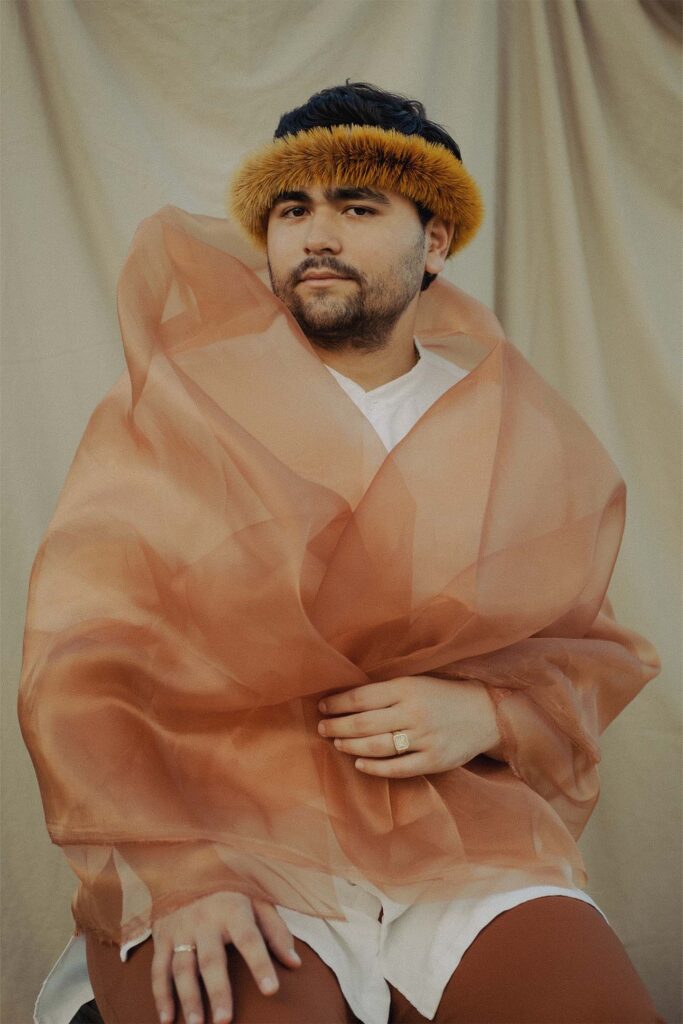

Growing up, Carrington Manaola Yap was surrounded by ʻike. This ancestral knowledge, passed down to him through generations of artists in his family, shaped everything about him—how he sees the world, how he moves through life. Ultimately, it influenced his approach to art, imbuing the designs for his Manaola Hawaiʻi clothing line with a cultural rootedness and authenticity that has made him one of Hawaiʻi’s preeminent fashion designers in the nine years since he launched the business.

“I was very fortunate to grow up in an environment that fosters that osmosis-style of receiving ʻike,” says Yap, recalling the formative years he spent gaining a grasp of styling and costume design from his mother, Nani Lim Yap, kumu hula for the award-winning Hālau Manaola. He laments how centuries of colonization have fractured the traditional means of receiving ʻike, which once came from ma ka hana ka ʻike—learning by doing. “A lot of our youth are not being raised in that environment,” Yap says. “It is a part of our kuleana (responsibility) to take that ʻike and innovate ways in which we can assure that these traditions will be carried on into the next generation.”

In 2018, Yap launched Hale Kua as an initiative of Manaola Hawaiʻi. The culturally driven incubator program is designed to give Indigenous artists access to the same sense of ʻike he was immersed in as a young creative.

“Coming back from Hale Kua, you see the world in this whole different perspective,” says Enoka Phillips, a Hawaiian featherwork artist who was selected for the project’s first cohort. Before Hale Kua, Phillips was educated in a Hawaiian immersion setting, instilling in him an early understanding of a Hawaiian worldview. In high school, when he became interested in lei hulu (feather lei), he approached master lei maker Florence “Aunty Flo” Makekau. Before long, he was forgoing beach hang-outs in favor of afternoons spent in Aunty Flo’s garage, learning the deft motions necessary to transform wisps of feathers into vibrant plumes of lei—receiving ʻike, as Yap would describe it. Later, his grandmother uncovered tins of lei hulu woven by his great-great-grandmother, revealing that Phillips’ affinity for the art form carries an ancestral origin. “It all came together,” Phillips says. “It was like, this is my calling.”

At the heart of the Hale Kua program is a week-long retreat on Hawai‘i Island designed to nurture this ancestral connection and sharing of ʻike. Guided by Yap, the artists dance hula, learn chants, visit heiau, and meet with kāhuna, deepening not just their art practice but their identity as Hawaiians.

After the retreat, Yap continues to mentor the cohort over the next five years, offering industry knowledge gained from his years of success in the fashion business. And for Yap, the artists’ commitment to their native craft is evidence of the power of ʻike and its role in keeping Hawaiian culture alive. “Cultural art heals,” he says. “We have to live and breathe [it] to receive the ʻike—not just to know what happened before, but to know how we’re going to innovate and navigate forward.”

Thinking Outside the Lab

A crowd is gathered in the remodeled second floor of the Mokupāpapa Discovery Center in downtown Hilo in 2022. Sleek wooden panels line the interior, infusing the space with convivial warmth. Hundreds of guests mingle in front of screens playing stylish surf videos on loop and installations of local artwork and handcarved surfboards.

Despite the atmosphere, this is no art opening or surfwear product launch. It is the unveiling of the Multiscale Environmental Graphical Analysis (MEGA) Lab, the new headquarters for a consortium of researchers making waves in Hawaiʻi’s scientific community.

A party for scientists may seem unorthodox, but that’s among the misconceptions the MEGA Lab hopes to rectify as it works to rebrand the public’s perception of scientists and, by extension, science. “One of the biggest reasons why there’s low scientific literacy is people don’t identify themselves with science,” says MEGA Lab chemist Cliff Kapono, who attributes the day’s growing mistrust around science to the wide gulf that exists between scientists and the general public. “If we show that normal people are scientists, [that] you are just like us, then that’s going to elevate people’s abilities to accept science.”

It’s an urgent objective for the MEGA Lab, whose research focuses on climate change and ocean ecology. As human activities threaten marine life at an alarming pace, MEGA Lab founder John H.R. Burns sees action beyond the scientific community as the avenue for real change. “If you don’t take a different approach, you’re going to keep doing the same thing, which is not fast enough to keep up with the problem that we’re seeing,” he says. This means innovating outside of the laboratory and designing new methods of communicating that effectively capture the public’s attention.

Fundamental to this approach is storytelling. A quick survey of the MEGA Lab’s online presence reveals the media savvy of a hip surf brand. Colorful images capture the researchers performing tasks that look equal parts work and play: swimming in Hawaiʻi’s waters alongside tiger sharks, traveling the world to study coral reefs, and no shortage of surf sessions in between. Contextualizing these aspirational posts, though, are captions on ocean acidification, coral bleaching, and ecosystems in peril.

A growing archive of documentary films and multimedia content also serves to broadcast the MEGA Lab’s pioneering research, which applies photogrammetry to render three-dimensional maps that aid in tracking ecological changes in coral reefs throughout the Pacific. The team’s documentary about mapping the reef at Fiji’s renowned surf spot Cloudbreak, created in collaboration with the footwear brand Reef, epitomizes the MEGA Lab’s approach when it comes to translating marine science into engaging narratives. “We’re trying to innovate how science communicates,” Kapono says. “Instead of being footnotes, we produce media products that are engaging, fun, and showcase sides [of science] that people can relate to.”

All of this is in hopes that a better understanding of climate science, and the habitats it seeks to protect, will galvanize the public toward a sea change. “We’re doing stuff with the purpose of having an impact,” Burns says. “We’re building new ways of studying and saving our reefs, but then giving that away [to make] sure that the impact goes beyond the doors of a lab space.”