Text by Sarah Burchard

Images by John Hook

Gabe Sachter-Smith grew his first banana plant at 13. His mom had ordered the cutting from a specialty banana farm in South Florida to satisfy his budding curiosity. It was a Musa ornata, or rose banana, beloved by gardeners for its crimson-hued florals. Sachter-Smith tried to grow it in the family sunroom amid the heat of a Colorado summer in hopes that it would mimic the tropical climes of its origin. The plant promptly died, languishing without the benefit of leaves or roots.

Undeterred, he ordered another cutting, this time a Dwarf Cavendish. It was a stout little tree that proved more durable than its predecessor. Soon, the 100-square-foot, two-story sunroom was filled with hundreds of plants sourced from online banana forums and specialty farms. They flourished under Sachter-Smith’s growing skills, helped along by an assembly of space heaters and grow lights—his personal tropical banana farm in the middle of Colorado.

Sachter-Smith’s obsession grew from an eighth-grade bet, when his classmates wouldn’t believe that the fruit didn’t grow on trees. He scoured the internet for evidence to prove them wrong. In the process, he realized that there was more to bananas than what he saw at the supermarket. “The truth of the matter is, I’m just inexplicably drawn to learning about and working with bananas,” he says. “I don’t know why.”

Eventually, his ambitions outgrew his family’s sunroom, and in 2007 he moved to Hawai‘i to study tropical plant and soil sciences at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. At every opportunity, he made bananas the focus of his projects. By junior year, the department knew him as “Banana Gabe”—a moniker that has stuck, even years later.

In his 20s, Sachter-Smith traveled across Southeast Asia and the South Pacific to study tropical varieties and learned that, outside of the Western world, bananas are more than just a breakfast food. In many cultures, the fruit is commonly found in every meal; in some communities, the word “banana” is also used to refer more generally to food.

It’s perhaps inconceivable to those in America, where despite the thousands of banana varieties that exist worldwide, grocery stores typically only sell one: the yellow Cavendish, favored by exporters for its high-yield, long ripening window, and attractive look on supermarket shelves. Today, Cavendish is the most widely exported banana variety. Decades-long monoculture, though, has left the crop vulnerable to diseases.

For a time, Sachter-Smith ran a booth for Counter Culture Organic Farm at Kaka‘ako Farmers Market, where he could be found, over jars of kimchi and baskets overflowing with carrots and kale, waxing poetic about Counter Culture’s 40-acre farm in Hale‘iwa. It was founded by Rob Barreca, a software developer-turned-urban agriculturalist. In 2017, when Barreca had his hands full building Farm Link Hawai‘i, an online marketplace enabling O‘ahu customers to order directly from local farmers, he asked Sachter-Smith, his friend and mentor, to take over the farm.

Sachter-Smith agreed, on the one condition that they someday grow a banana enterprise. During the pandemic, the farm’s wholesale orders dropped as Farm Link Hawai‘i’s sales soared. Barreca, entrenched in his startup, gave Sachter-Smith free rein, with a simple directive: Go bananas.

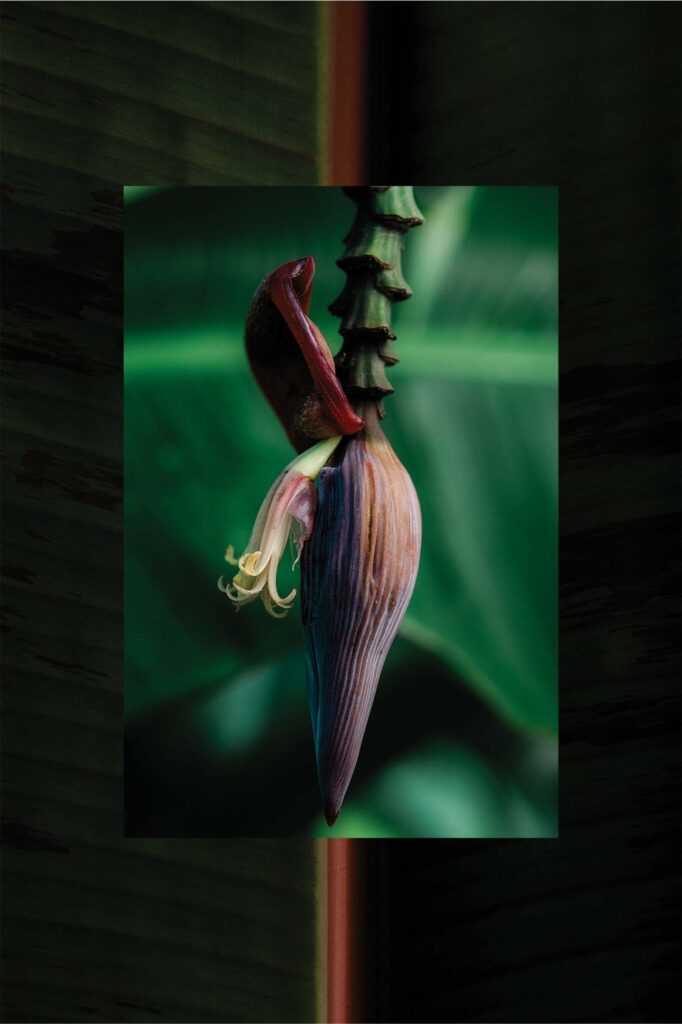

At Hawai‘i Banana Source, the farm’s new iteration, some 150 banana varieties are cultivated under Sachter‑Smith’s helm. Among rows of swaying banana stalks grow wild cultivars, including a dozen Hawaiian varieties such as iholena, whose long fruits are starchy and plantain-like when cooked, and the endangered ‘ele‘ele, thought to be extinct until it was rediscovered in 2004. The farm also doubles as Sachter-Smith’s laboratory, where he experiments with rare cultivars and hybrids in attempts to create the perfect specimen.

He admits that it’s rare for a banana farmer to also be a breeder: “I am the only person I know doing all the things I do with bananas.” In the nursery, a peek under the lid of a bathtub-sized bin reveals an assortment of new banana varieties he has hybridized. “I am constantly making more, selecting keepers and tossing most of them,” he says. “I probably have around 200 to 300 at the moment.”

At present, Sachter-Smith is developing a banana plant that could be grown by anyone in the tropics, even in a pot on their lānai. “My ideal plant would be about five or six feet tall,” he says, for more convenient growing. It would be ready to harvest within six months, with a lighter yield than that of common varieties but a more frequent fruiting schedule. “Instead of growing 50 pounds of bananas once a year, you’d have five pounds ten times a year,” he says.

In the meantime, his customers are content with the varieties, rare or otherwise, that he is already cultivating—happy, no doubt, any time Banana Gabe debuts the latest fruits of his labor.